The Search For Significance Inside of The Social Network

“I think socializing on the Internet is to socializing what reality TV is to reality.”

– Aaron Sorkin

Expectations were sky high when it was announced that a movie would be made about Mark Zuckerberg and the drama behind the inception of Facebook. Scott Rudin would produce it, Aaron Sorkin was penning the screenplay, David Fincher was set to direct, and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross of Nine Inch Nails were going to score the film. The pedigree was there, and the marketing campaign only helped it gain momentum with its eerie trailer and audacious poster, both hammering the message home: “You don’t get 500 million friends without making a few enemies.” The number of Facebook users has only grown since 2010 and now a decade later, all of the consequences of its wide reach are becoming more and more apparent.

The opening of this film is easy to underestimate on first viewing, it seems like just another quasi-asexual date between the couple of Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) and Erica Albright (Rooney Mara). Mark’s debate and condescension of Erica’s college experience, and how it pales in comparison to his Harvard life, eventually causes her to break up with him on the spot. In a disappointed and emasculated frenzy, Mark writes a scathing and insulting blog about Erica before he and his roommates create a campus website called Facemash. On this site, users are able to rate the appearance of girls on campus against each other.

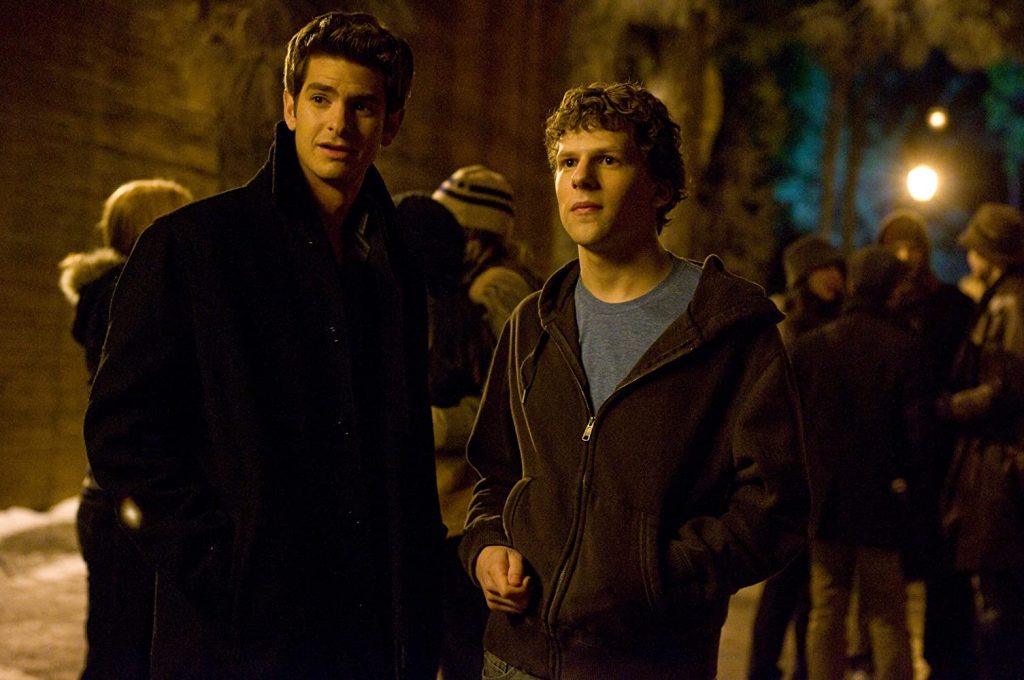

When Mark is put on academic probation following the incident, he is approached by Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss (both twins played by Armie Hammer) and their business partner Divya Nerandra (Max Minghella). The trio recruit Mark to create their own Harvard-exclusive social and dating site: The Harvard Connection. Not long after that, Mark recruits his best friend Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield) to create their own Harvard-exclusive social and dating site: Thefacebook. When Thefacebook goes live before The Harvard Connection does, the original trio sue Zuckerberg, and the depositions between all interested parties intercuts with the events of the film. The two timelines show how partnerships are formed, lines are crossed, friends are betrayed, and the significance of the intellectual property later known as Facebook is born.

Aaron Sorkin has made it clear that his films based on real people are less concerned with factually portraying the actual events, but more focused on making sure the essence of these real figures rings true within the dramatization of their lives. Sorkin has no easy task with this adaptation of the Ben Mezrich book, The Accidental Billionaires; he had five different people go into a deposition and five different narratives come out. So rather than pick one, he shows them all, and roots them all in the psychosis of these characters, all of which are looking to be significant through this (allegedly) shared IP.

Mark’s behavior throughout the film indicates his hurt at the hands of the social norms of day-to-day life. His attempts at humor fall flat, his attempts at connection through friends and significant others eventually dissolve; simply nothing he does to play by the rules of the social contract works out. So he decides to pit these conformities against his peers through the sophomoric Facemash, and then try to gain their respect through Facebook as it expands to universities across the nation. As we know from history, this ultimately works. The same people who called him an “asshole” for rating their looks against their peers join the site. The herd mentality has a short memory, so long as you feed their addictions.

The addiction that powers Facebook is best explained by the six basic human psychological needs as outlined by Tony Robbins: certainty, variety, significance, love/connection, growth and contribution. When someone logs onto Facebook, they are certain to find new posts from their friends that align with their personal beliefs. There is also an inherent excitement behind the variety of thoughts and subjects amongst those updates. If they make a post of their own that gets a large response, they will feel significant. If they form a new friendship, or interact with an existing one, then it goes without saying that represents connection. If something taps into only two of the six needs, an addiction likely follows, thus making it easy to see why Facebook and social media as a whole swept the nation.

It is understandable why people bought into the Facebook/social media platform; it gave them an outlet to express their knee-jerk response to the world around them. These platforms are only as thoughtful or considerate as their users choose to be, but the impersonal nature of online discourse reward apathy and anonymity. You can say whatever you want to anyone, but you will not be forced to deal with how they receive your words, and therefore miss out on the entirety of non-verbal communication (which makes up 60% of all communication). It’s not a new opinion that social media is really anti-social media, but now that we have more than a decade of recent history to examine the lasting effects of the landscape created by Mark Zuckerberg and the technocracy, we can see how reductive it is to true progress. People are becoming less equipped to deal with the real world and because they have been enabled to do so, they now feel empowered to exact revenge on another person’s reputation and livelihood if they do not share core values.

I am all for everyone having a voice, I just don’t think everyone has earned the microphone. And that’s what the Internet has done.

Aaron Sorkin

The term “technocracy” holds weight because the influence of digital media platforms over legislative and financial decision-making is extremely evident in the current era. It’s hard to argue with that when theatre chains such as AMC are bullied by social media mobs into reversing their position on the usage of face masks upon their reopening. It would be irresponsible to underestimate that kind of reach and status within the national discourse. This goes as far back as 2011, Facebook’s coverage of the Egyptian Revolution had been acknowledged as a force in turning the tide of that conflict, in terms of public relations management.

The various back-stabbings and double-crosses portrayed in the film are truly hurtful, and the dissolution of these relationships have a ripple effect across the world, quite literally. This hurt is apparent in the portrayals of these characters; Jesse Eisenberg’s quiet demeanor shields a loud and painful core within his portrayal of Zuckerberg, and Andrew Garfield became a movie-star as Mark’s instantly likable and trusting friend, Eduardo. David Fincher’s sickly-green and disconcerting visual style behind the lens amplifies the hollow victory behind Facebook’s birth. Although we know how successful the platform has become, we know its at the cost of the human spirit. Despite how punchy and enrapturing Sorkin’s dialogue is, he makes sure to balance it out with succinct reminders of the depravity behind the anti-social behavior it rewards. Reznor and Ross’ score underlines all of this with distorted synthesized cords, and purposely haunting piano keys.

The film was always meant to represent a shallow way of living, but it has since become a bleak predication of what was to come. None of the artists behind the film could have known exactly what that world would have looked like, but it’s apparent that they knew it wasn’t headed to a positive place. Whether knowingly or unbeknownst to him, Mark Zuckerberg created the battleground where thought-policing gained its foothold in the modern era. Making people feel significant for apathetically demeaning and destroying the livelihoods of others became the bizarro-world version of the mainstream. The human experience is faced with a pivotal challenge to overcome and if the technocracy has its way, no one will be able to say or do anything without their approval. The even scarier conceit is that they’ve convinced their users that they all approve of the same values and behaviors. It will be a rude awakening once we break this addiction and it is going to take a hard look in the mirror, the same hard look that Mark Zuckerberg maybe should have taken.

Comments