The Psyche of Entitlement: Roman J. Israel, Esq.

We all lament over the death of studio films that challenge, provoke, and require a humble mind in order to appreciate and enjoy. However, when one comes along it seems as though it is taken for granted and allowed to leave the discourse over the matter of a few glaring shortcomings. Enter Roman J. Israel, Esq; a film that oozes optimism and insight into the cultural cycle of entitlement and enlightenment. A film that was the victim of a harsh critical response, and thus left behind by the mean-spirited nature of modern film criticism and social attitudes.

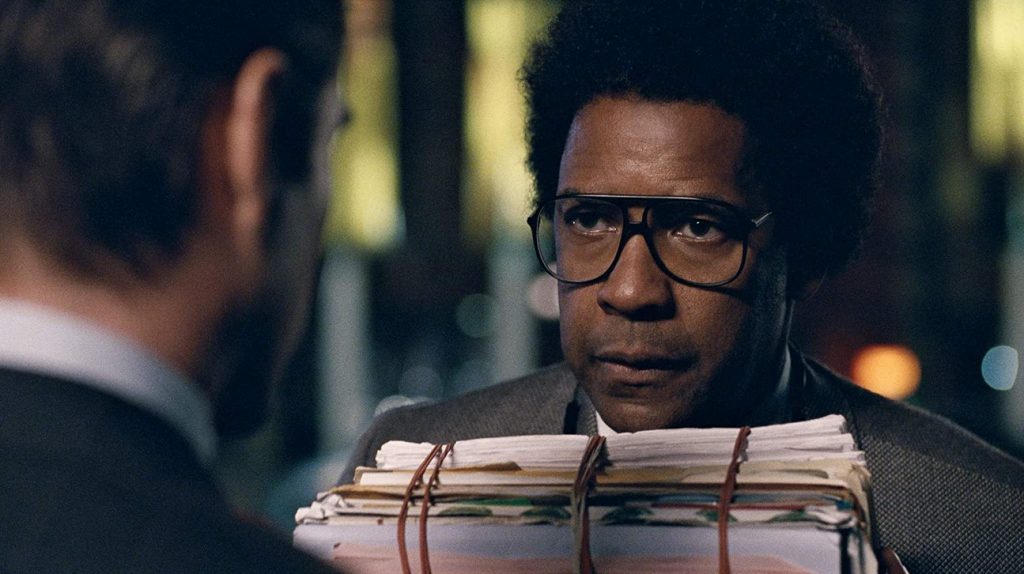

For 36 years, Roman (Denzel Washington) has been the man behind the scenes of the law firm started by he and his partner, William Jackson. William was the face in court, and Roman was the one preparing the legal briefs in his eccentric and lovably awkward ways. Roman’s annoyingly ethical demeanor has him butting heads with prosecuting attorneys and judges alike, and that Achilles’ Heel has forced him to stay out of the public light, despite his penchant for civil rights activism. After falling ill, William’s practice must be dissolved and absorbed in order to pay out Roman and the other staff any severance. The business he had spent three decades building is going to be taken over by the practice run by George Pierce (Colin Farrell), a former student of William’s who always greatly admired his work.

Rather than simply discarding Roman, George sees the value of his moralism, and offers him work at his firm. George has been quietly keeping William and Roman’s practice afloat for years, despite taking a monetary kickback for every case George passed on to them. The discovery of this arrangement rubs Roman the wrong way, and it taps into a deep-seeded resentment that he has long felt. Nothing about George is inherently wrong, but he seems almost too good to be true. His candor and speech are so well refined and slick that Roman sees him as a fraud. What develops over the course of the film is an examination of why people feel like they deserve more than what they have received in life.

During a search for other avenues of employment, Roman interviews at an activist office where he meets the community organizer, Maya (Carmen Ejogo). Desperate to not “sell out” to George’s firm, Roman tries to return to his past as an arbiter of civil rights by offering his legal services to Maya. After Roman pours his heart out, Maya is forced to turn him down due to budgetary constraints, but she is so moved by his spirit that she asks him to speak to her staff and community at an upcoming gathering.

The film establishes two ideological pillars in George and Maya; two people from different worlds who both try to do the right thing, however with disproportionate levels of success despite the abundance of idealism within both of them. These are the two worlds Roman has been a part of for the past 36 years, but has never fully been accepted by. Because of that he judges George’s success to be dispassionate, and he foolhardily believes Maya is in the most righteous position. The thing he’s missing however, is that George’s firm is successful because of his quiet and genuinely judicious mind, and that Maya’s organization is middling because the work ethic has yet to catch up with their outward empathy for minority communities.

What both George and Maya share is their admiration of Roman, and the tragedy of Roman’s character is that his unique attitude in life keeps him from seeing his own inner glory. He tries to outwardly replicate George’s status and earn the favor of Maya’s virtuosity, but misses out on the inner values within them that he can learn from to create his own self-actualization. Instead, he succumbs to a financial temptation halfway through the film. A consequential decision that starts to swell and consume Roman’s mind, and feed into his self-loathing tendencies. After spending decades fighting for what he truly believes in (impartial and unprejudiced justice), he has not replicated the fulfillment or status that he believes he is entitled to. He takes a short cut, at the expense of the thing that makes him so beloved: his purity.

This is a dialogue-heavy film, and there’s a lot of legal jargon and exposition that becomes muddied quickly in certain sequences. Dan Gilroy is directing his own screenplay here, and as fleshed out as the writing is, its intricacies can sometimes get away from itself. Writer/Directors often get criticized for treating their writing too preciously (Quentin Tarantino, most famously), and it’s easy to see why so many critics dismissed the film for this aspect. For example, Roman carries a briefcase around that is essentially the visual representation of what he has to contribute as a lawyer, as an ideologue and as a man. However, its explanation comes at such an awkward time in the film, that its importance can be missed entirely on first viewing. Despite the few overwrought flaws of this film, its optimism and empathy for its subjects is so refreshing amongst a sea of recent cynicism coming out of Hollywood.

The film rises above the virtue-signaling trend that exists in the current entertainment and political landscape, and really tries to explore the nuance of the entitlement attitude that plagues the modern era. At one point, whilst speaking to a younger crowd, Roman’s classical ideas trigger the vitriol amongst the young people who believe the world owes them a lot more than they have received. Rather than hear Roman out about his days as an activist, they dismiss and insult him using modern buzz words. Perhaps they are doing this to let themselves off the hook from expanding their minds? It’s possible, but the movie does not comment on this further.

As we see in the back half of the film, Roman is not immune to the epidemic of entitlement. Roman has a bone to pick with attorneys using plea-bargains to preserve their win/loss record, rather than actually advocating for their clients’ innocence. He has been working for years on a court filing that proposes an amendment reforming the plea-bargaining system, but rather than see that fight through to the end, he allows this proposal to collect dust on his shelf after he gives in to his entitled temptations. Denzel’s performance is so compelling and the audience sympathizes with this character so much that we understand, accept and even forgive him for this attitude. We believe he is better than his darkest and most selfish thoughts because he remembers every client’s name, and he does his best work for everyone who asks for it.

Watching Roman J. Israel, Esq. makes you realize that it doesn’t take much to engross an audience. A strong narrative, clever writing, and committed actors who allow the story to speak through them will keep people engaged and satisfied. Colin Farrell does truly underrated work as the perfect cypher for Roman to decode, as he contains the outward appearance of being a dispassionate snake charmer, but none of the behavior of one. Carmen Ejogo plays such a great empath that it breaks your heart to see her stuck with a staff that will never care as much as her and Roman do about civil rights. They simply want a good cause on their resume, whereas Roman wants to have a lasting impact on the world.

The tragedy of this film is that its critical response was dismissive of its solution-based thinking. Rather than point fingers at the institutions that may or may not be responsible for inequality in the eyes of the law, it simply says that if the right people cross paths, the compatibility of their beliefs and skillsets can be enough to create real reform. The ultimate sentiment behind this film is that no matter how many walls the elders of our time run into today, there will always be someone to pay it forward tomorrow.

Comments