Hypocrisy Exists Within Your Minority Report

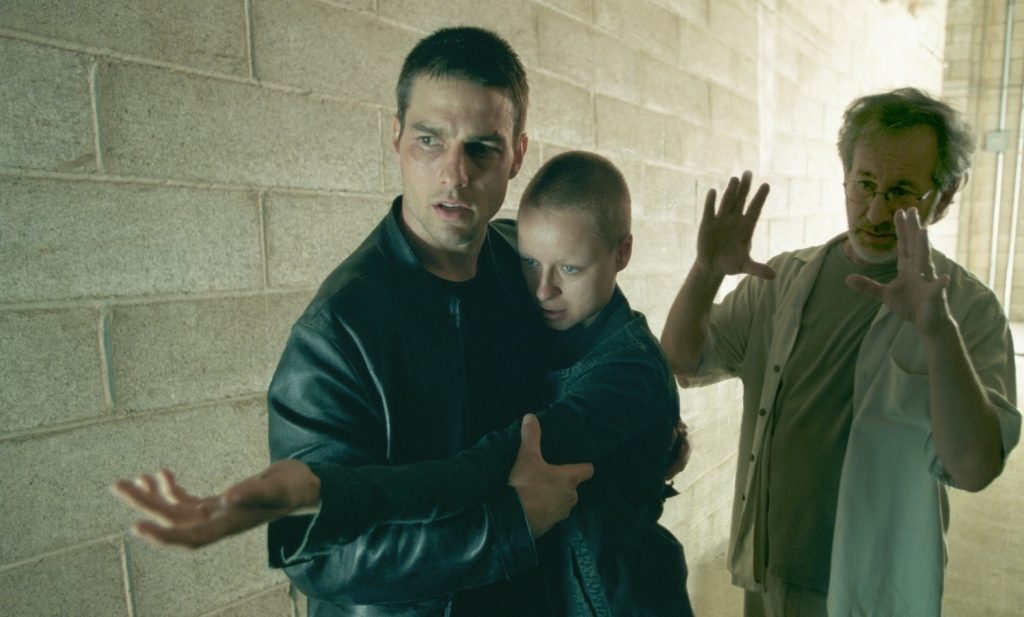

There have been plenty of think-pieces written on the 2002 soon-to-be-classic Minority Report, directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Tom Cruise, about its predictive powers of what the near future will look like. Self-driving cars, targeted advertising, identifying and surveilling individuals with technology, and preventing crimes before they happen were all fun novelties when the film came out, but are advancements currently being tested by world governments (including our own). There are several obvious things within the film that we could point to as systems that should scare us in 2020, but that is not the focus of this blog. We are here to identify the moralism behind the social evolution of mankind through film. What this film can help us recognize is that within all of these technological and sociological innovations is some manner of hypocrisy in its implementation. The way to combat these systems is to identify these hypocrisies, and if we examine their existence within Minority Report, we may find solace in how these systems may eventually cave in on themselves.

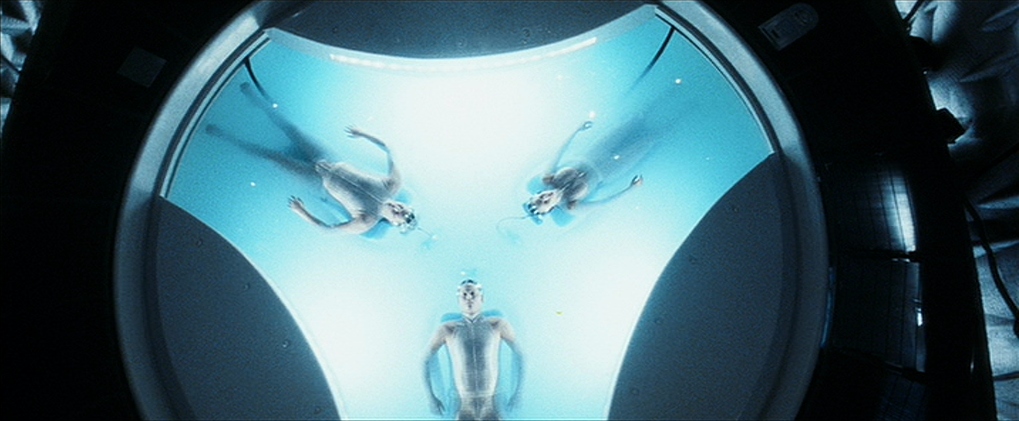

No one has done more for science fiction cinema than the author Philip K. Dick. Having written the novels and short stories that eventually became the likes of Blade Runner (1982), Total Recall (1990), A Scanner Darkly (2006), The Adjustment Bureau (2011), and today’s subject, it’s clear that he had a clear sense of what he was trying to say about where society was headed. The common thread through all of these films is this: the ruling class above us will challenge our free will, will do so under the guise of altruism, and manipulate the masses by guiding their insecurities, fears, decisions, and even their passions into doing their bidding. In Minority Report, our gateway into this vision of dystopia is Washington D.C. Pre-Crime Police Chief, John Anderton (Tom “Running Man” Cruise). Anderton had suffered the loss of a child several years prior to the film’s year (2054), which led to the dissolving of his marriage, his drug addiction, and his promotion to lead a revolutionary kind of police division; one that houses individuals with precognitive/psychic abilities (“Pre-Cogs”) who are able to predict violent crimes before they happen.

Washington D.C. is the testing ground of the program, and to Pre-Crime’s credit it has been working; there hasn’t been a single murder for the six years it has been around. Anderton believes in the system, he believes it could have saved his son’s life had it been around sooner, and he believes he is doing righteous work. This is all challenged by Colin Farrell’s character, Department of Justice agent Danny Witwer, who believes however flawless the system may or may not be, Anderton is not the man for the job given his obvious and tragic conflict of interest. Danny may have a point, as we see that the Pre-Cogs predict that Anderton will commit a murder himself, forcing John to go on the run and clear his name. It’s classic chase cinema, with all the suspense and tension a good whodunit film requires; a formula and genre that Cruise had already spent the decade leading up to this film perfecting.

As prescient as the film’s themes and content is now in 2020, there are still a few things that could have stayed in 2002. The jetpack chase sequence halfway through the film is quirky and creative, but a bit too light in tone when put up against the rest of the film. There is also a fist fight between Cruise and Farrell that may take the “Unintentional Comedy” award for both of their careers (which is no small feat when we live in a world where Far and Away (1992) and Alexander (2004) exist). Fortunately, the special effects work won’t take you out of the film as they hold up pretty well. A stand-out sequence involves CGI spider drones searching for Anderton throughout an apartment complex, where the spiders and John Williams’ score are both appropriately terrifying and suspenseful. What makes this particular scene retroactively frightening is the known role that unmanned drones have in modern warfare and in domestic surveillance. Spielberg had a panel of futurists he consulted during pre-production on this film, and it’s in scenes like this where they proved to be ahead of the curve.

We’ve been meaning to discuss Tom Cruise’s role as an American film icon on this blog for some time, and without spoiling a future piece, we cannot commend him enough for building a career on high-concept entertainment such as this film. Spielberg always knows where to put the camera and how to give a scene energy, but Cruise knows how to imbue meaning to the subject of the lens. His focus and commitment as a performer shows up in John Anderton, a man forged by self-doubt and family tragedy but fulfilled by higher purpose and exceptionalism. It’s clear that Cruise has always enjoyed his profession, but rather than yucking it up in front of the camera, or letting the film become an ego trip like other projects of his, he plays it straight and brings intensity, grief, and rage into this role. But what really sells this character is one of his most fundamental human qualities: being a hypocrite.

In his race to clear his name, Anderton discovers that not all of the “guilty” people he has convicted without trial were certainly guilty. The flaw in the system is not that the Pre-Cogs cannot see a divergent future where the alleged killer may choose not to kill, but rather the record of this possible outcome is erased by Pre-Crime technicians. This flaw is not a flaw of the Pre-Cogs themselves, but rather a human design error that can be exploited by the individuals who can benefit from the expansion of the system across the country.

As with anything at all in the world, if done with the wrong purpose in mind, the right thing may become exploitative. The same goes for the inverse, anything with harmful intent may be re-purposed for good. What separates these positive and negative outcomes is the desire of the individuals in charge of them. If William Barr’s DEEP (Disruption of Early Engagement Programs) is an extension of the powers of the intelligence and security bureaus meant to protect us, then isn’t that a favorable advancement in the eyes of the American public? In an informational vaccuum, yes. However, knowing the history of the intelligence community starts to contradict the official narrative pushed alongside DEEP. When you look at the human experiments that took place at the hands of the 1,600 Nazi scientists detained under Operation Paperclip, or the CIA’s experimentation of children under Project MK Ultra, or even the Enhanced Interrogation Techniques displayed in the War on Terror, it’s hard to trust the narrative that these agencies have our best interests at heart.

As we see in Minority Report, people high up in the status quo such as John Anderton may have noble convictions behind their involvement in government-related social experiments, but that does not mean his superiors share those sentiments. In fact, they exploit Anderton’s personal demons in order to use him as the scape goat for a larger conspiracy. In the eyes of the public, one bad apple taking the fall for crimes against the state is enough evidence to suggest that good has triumphed over evil. If the public’s only visual reference point for evil is met with justice, then they can comfortably go back to the herd with feelings of satisfaction, yet unaware of how they’ve been played by those driving the PR-narrative vehicle. Evil does not stop when you attack its servant, it stops when you go straight to the source. Anderton is hell-bent on going straight to the top, and the film will make you want to follow him there.

When it comes to hypocrisy as exemplified by the film, we can look to John Anderton, Danny Witwer, Lamar Burgess (Max Von Sydow), Iris Hineman (Lois Smith) as our embodiments of the plot’s conflicting interests. These four characters genuinely believed, at one point or another, that the Pre-Crime system could be used for good, but as soon as they got their hands on it, any altruism that may exist within their own premise is overshadowed by their desires. For Anderton and Witwer, it is revenge against the criminals that brought tragedy upon their respective families. For Burgess and Hineman, the system’s architects, it is the proximity to excellence and status they gain from being a part of such a successful system. However, in Hineman’s case, the guilt over what the system became overtook her, and she sought excellence elsewhere. It’s in her character that we can see that she is visibly ashamed of what she helped build, and for Anderton to see this in Hineman forces him back to his true principals, this time not blinded by Pre-Crime-tinted spectacles.

Science fiction has always been a source of resonant themes because it is an effective way of questioning the audience’s understanding of the meanings of identity and the “here and now,” by taking them to a place that is outside of themselves and “not here and not now.” The cautionary tale that exists within these premises is that although the future is not this moment, it eventually will be and the time to combat future injustice is by being vigilant now. If we, as a people, are facing dissent and collapse within our current world, it is because we were not vigilant enough of the true causes and were not critical enough of those who claim to provide salvation. How may our government benefit from a fearful and misinformed public being led by an extremely pervasive intelligence apparatus? If we are facing crisis now, how does their power grow from their own proposed solutions? If the same people who tell us what to be afraid of, also offer a seemingly perfect solution to said problem, then how can we afford to buy into that coincidence? The mere fact that we are asking these questions is proof enough that we have not been doing our jobs as American citizens, and that our once-great Republic has gotten away from us.

Comments