Who is Responsible for Joker?

“All I have are negative thoughts.”

Action and reaction make for great storytelling. When the audience can trace the reason somebody does something followed by their response to the given circumstances, it makes for compelling viewing. The complexity of film comes from the difficulty of the themes explored by the story, and the quality of the film is dependent on the depth of the exploration. Joker aims to get the bottom of violence, and who or what is to blame for the worst that humanity has to offer.

The film opens with a man in front of a mirror, his face obscured by clown makeup as he tries to bring a smile to his own face, eventually having to force one by sticking his fingers into the corners of his mouth. Meet Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), a party clown-for-hire with a mental condition that forces him to laugh uncontrollably in moments where most people would not. The first thing we hear him say is a question he poses to his social services counselor (and to the audience): “Is it just me, or is it getting crazier out there?” When we see him get harassed and beaten by teenagers, his living conditions, and the quality of person he is surrounded by at work (save for one extremely kind dwarf), it’s hard not to wonder the same thing.

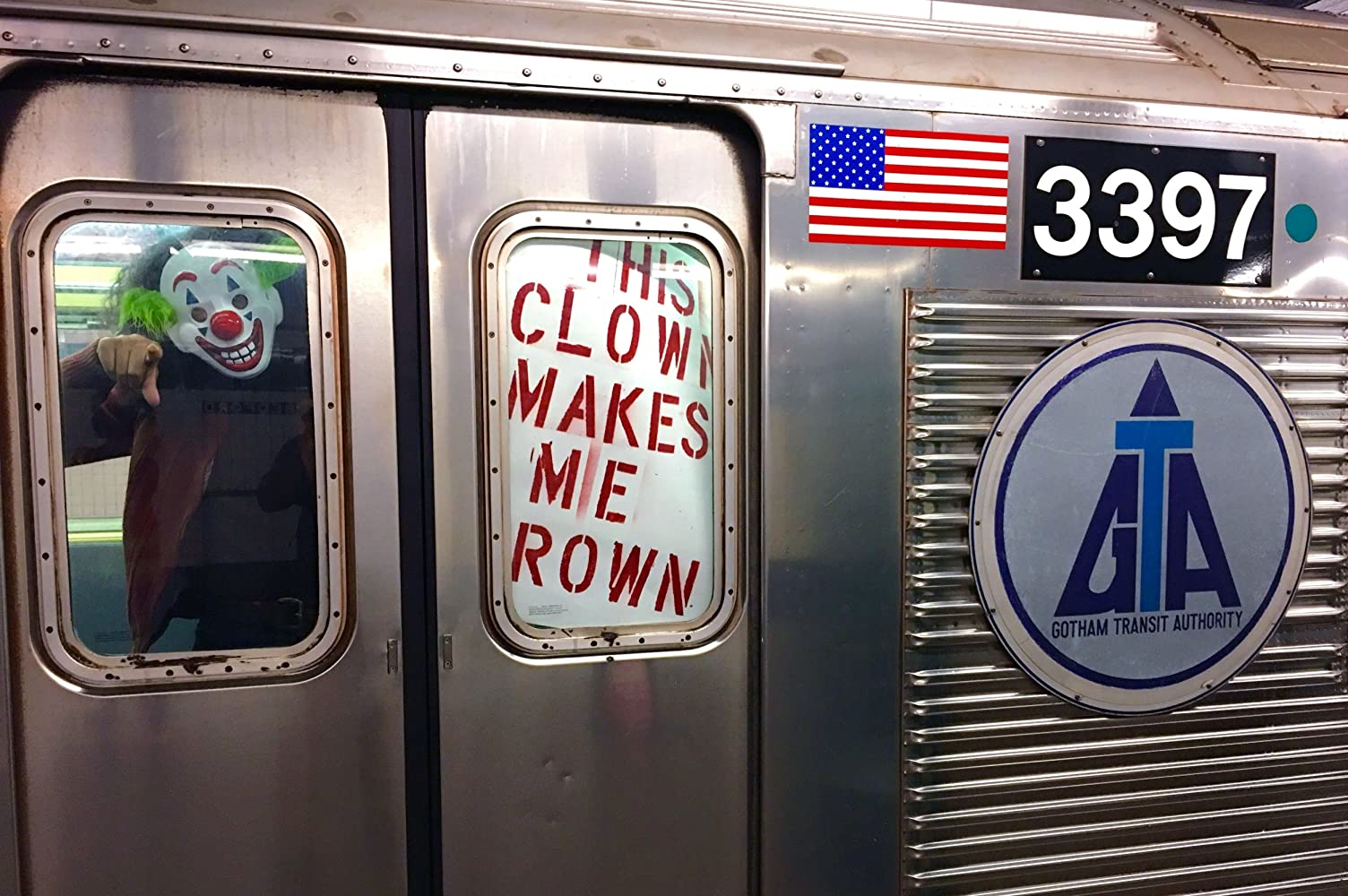

The film tricks us into viewing the world from Arthur’s perspective. We are there when he is bullied, we are there as he cares for his ailing mother (Frances Conroy), and we are there as he dreams of being accepted by his comedic idol (King of Comedy himself, Robert De Niro). If we did not know this movie was about the Joker, we would find it heart-warming that he believes he is meant to “spread joy and laughter.” But as vision of Todd Phillips’ 1981 Gotham City starts to illuminate itself, we slowly understand that things are not as they seem. In Gotham, (really it’s New York City, but I’m happy to play along) all we can see is decay and civil unrest. Your safety is always in question, and when a co-worker offers Arthur the means to “protect” himself (an unregistered revolver), Arthur protests but ultimately accepts this gesture. Not too long afterwards, Arthur is on the receiving end of his second public beating in the film, only this time he does not go quietly. A lesser film would make the argument that if Arthur was never offered the gun he never would have hurt anyone. Phillips knows better, and introduces several red herrings and counter-arguments throughout the film. Where most writers would use Thomas Wayne’s campaign for Mayor as a plot device to condemn the one percent, we eventually learn why his successes are not at the expense of people like Arthur. Most writers would turn the Joker into a symbol of anti-fascism and an excuse for anarchy, but Arthur plainly tells us that he “has no politics” (about as meta-textual a line you can get in a film riddled with them).

Once we become accustomed to Arthur’s ineptitude at socialized behavior, the film throws revelations at us that create distance from his perspective. The character study we have been watching for the first hour turns into something much more understandable: a comic book film starring the villain. The empathy we once had for his abuse and horrid living conditions is gone, and we see that he has not been coerced into violent tendencies, but that he has always had them within. The difference now is that adversity has caught up with him, and he now feels empowered to liberate his true self. Could we infer that his witness of the turmoil around him is the reason for his heinous actions? One could make that argument, and if the film did not go to such great lengths to establish the severity of his illness and highlight his disconnect from other people, I would agree. But every time we see him laugh at things he finds funny, it’s the times when nobody else is laughing. When he dances, it’s by himself in a twisted and off-putting fashion (Put Joaquin on a couch, and there’s nothing the man can’t do). The unfortunate thing is that while the audience sees the truth of this world, Arthur is incapable of accepting the way things are.

You have to commend Phillips’ thoroughness when introducing story threads that potentially absolve Arthur, only to purposefully contradict them. Even more so, Joaquin’s commitment to the role keeps us involved in this world, and anxious to find out where he has been leading the audience. The final act of the film is a gripping and terrifying affair. The transition from Arthur to Joker is documented masterfully, shot with intrusive close-ups by director of photography Lawrence Sher, and set to a haunting score from Hildur Guðnadóttir, in addition to some poignant and comically twisted needle-drops (shout-out to Cream’s White Room).

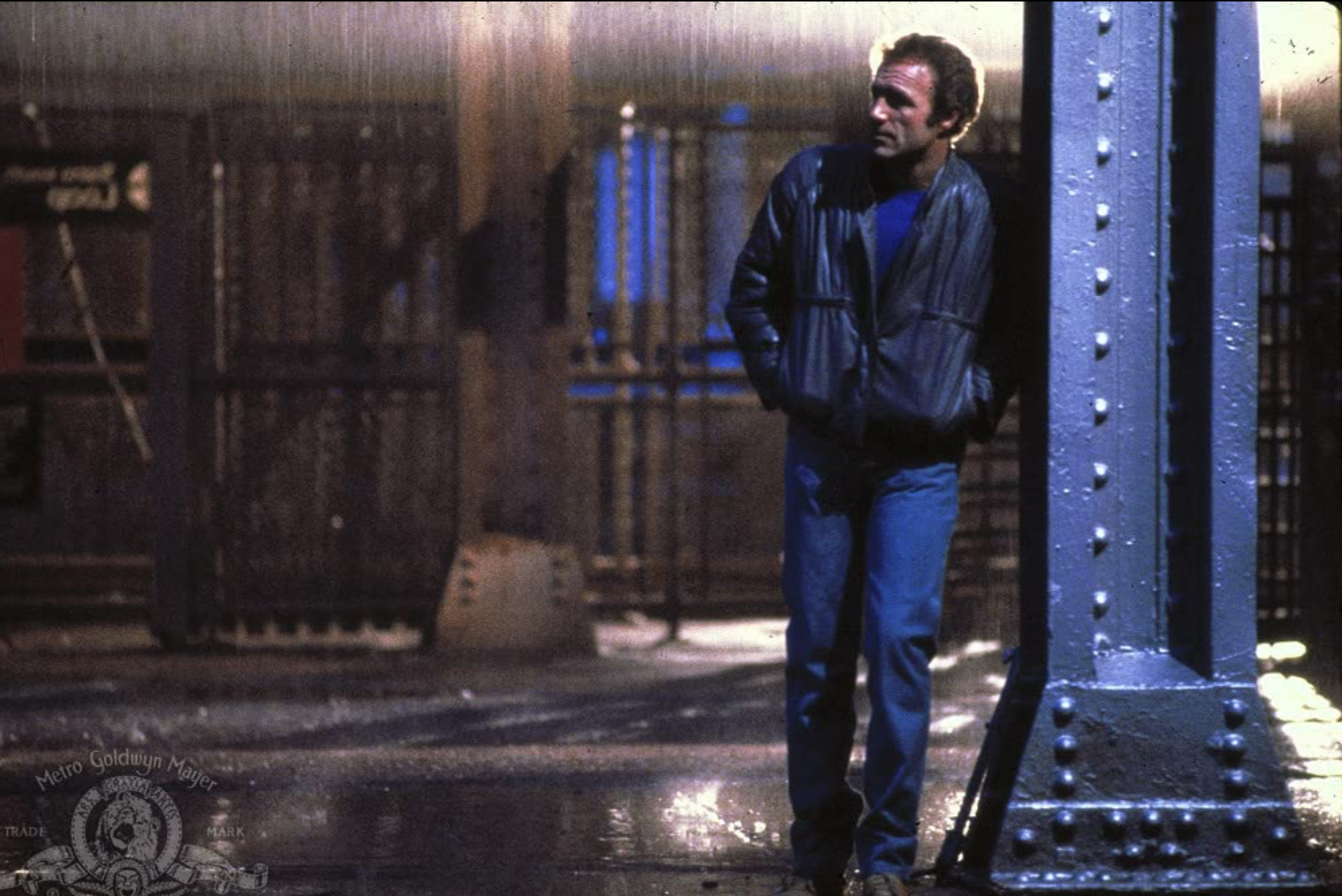

It’d be a crime not to mention the impeccable supporting cast, such as Brett Cullen as a less polished version of the iconic Thomas Wayne, De Niro (representing the era of Scorsese cinema the film proudly pulls from) as the late night talk show host Arthur idolizes, with Bill Camp and Shea Whigham as the GCPD detectives investigating Arthur’s crimes. I have to give special recognition to Zazie Beetz and Brian Tyree Henry (who collectively hold a large chunk of my movie star stock) for being incapable of anything less than grounded, present, and enviably likable performances in every role they accept.

A film can only be this engrossing when the director has a vision as unifying and clear as Todd Phillips’, and a team that dedicates itself to fulfilling it. This is a responsible film, made by responsible artists. They do not believe the injustices of the world can be solved with a magic bullet, or a succinct and vapid platitude. The world is a complex place, and even the most disturbed and demented people have sympathetic qualities. Most filmmakers would answer the question “Who is responsible for the Joker?” by placing blame on societal constructs like capitalism and politics. Others might be succinct and say “Duh, the Joker!” Although they wouldn’t be entirely wrong in holding the individual who perpetrates violence accountable, it is far from being that simple. Arthur may just “want to watch the world burn” for what he thinks it did to him, but to dismiss him as crazy and unrelatable would be inhumane and irresponsible of us.

Comments