Managing Relationships: Heat

Action cinema has long been a genre that glorified strong and silent heroes. Classical stoics who work through their inner struggles by leaving a trail of bodies in their wake and being the coolest guy in every room they walk into. In the 1990’s however, there are a few notable films that try to reconcile action cinema’s desire for violent catharsis, such as Client Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1991). But the one that does so in a less obvious and arguably more impactful manner, is Michael Mann’s 1995 crime epic. A film where cops and robbers become the excuse to examine the balance between our work and our personal lives, rather than the focus.

The first time you watch an action movie, you’re watching it for the action first and foremost. If the film excels at its genre, then most people will find themselves watching it again for the character moments and the story between those action beats. Heat is nearly three hours long, and not even a third of its runtime is dedicated to its masterful action sequences. Has it hurt the film’s place in film history? Not one bit. The reason for this is that Michael Mann understands that storytelling is most relatable and engrossing when it is an extension of the character’s pathology. He personifies side characters who in any other film would not hold any place in the audience’s mind, but instead maximizes their humanity in a minimal amount of screen time.

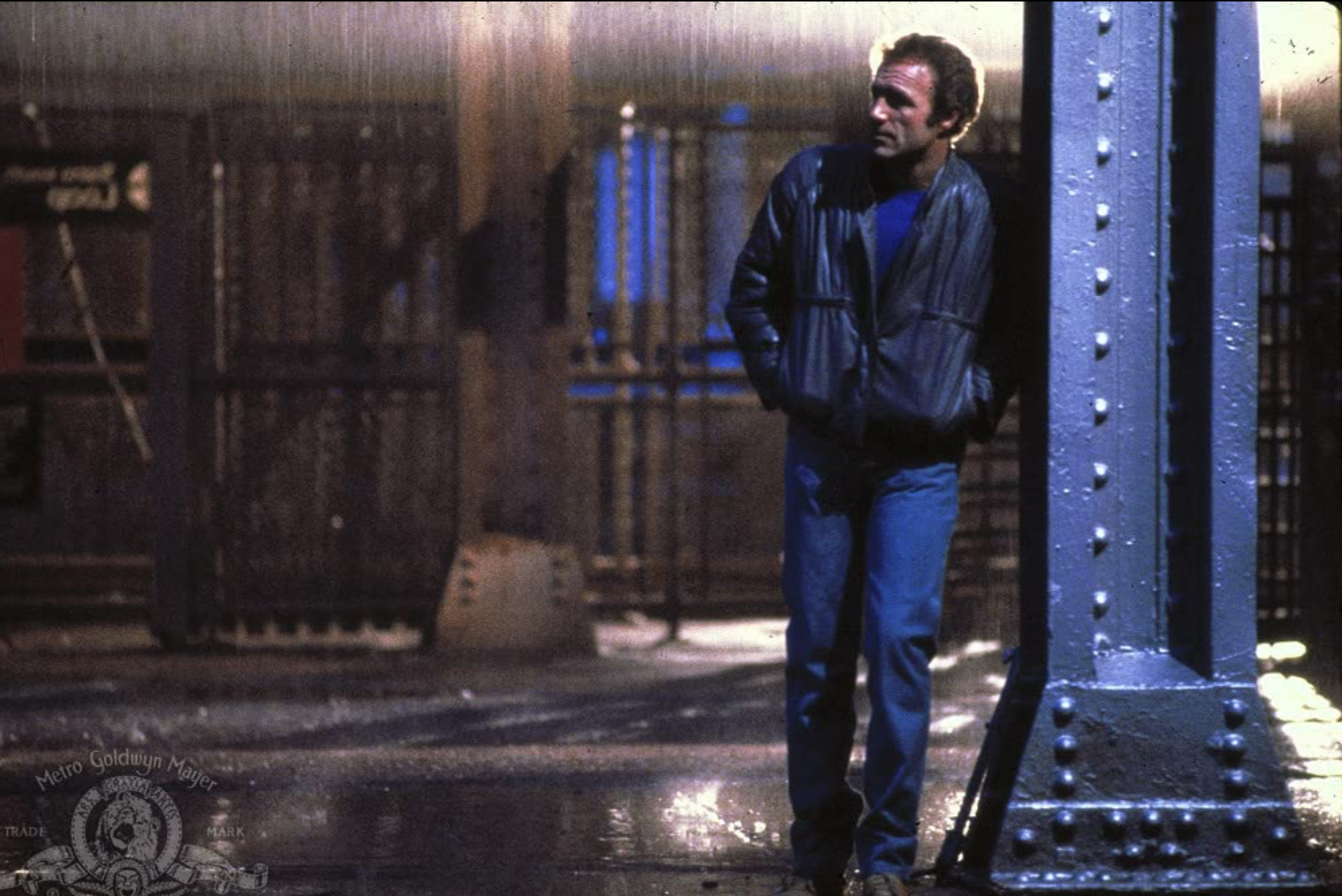

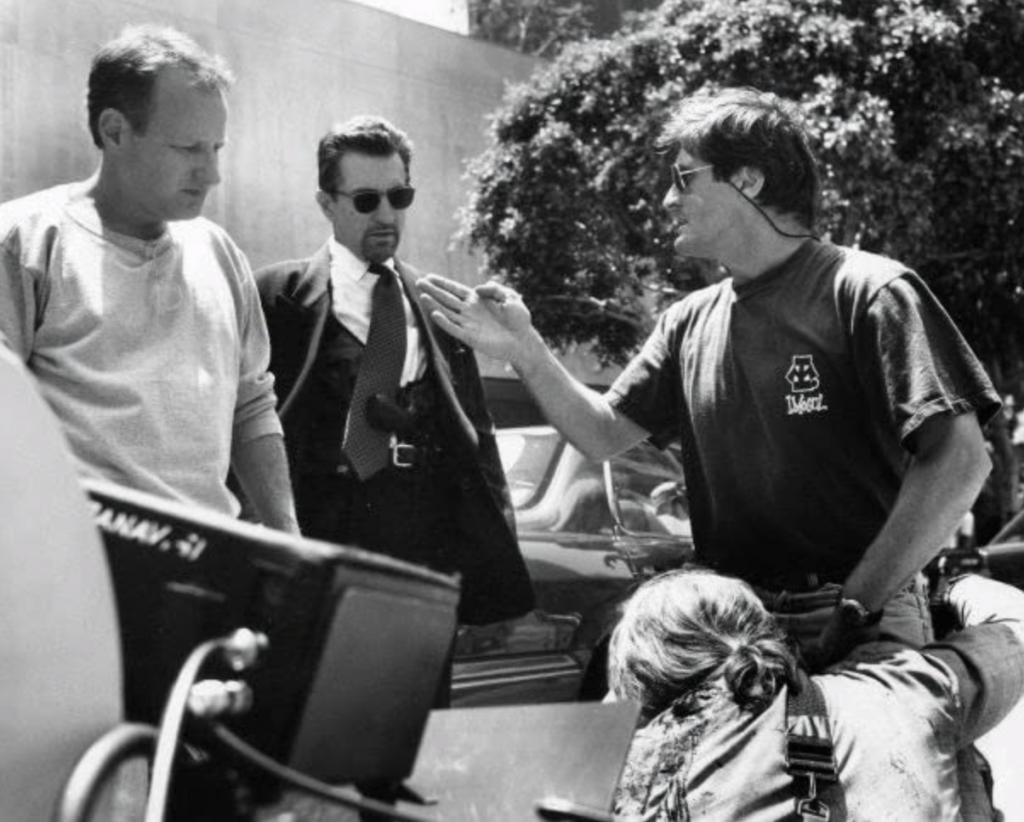

Al Pacino’s Vincent Hanna and Robert De Niro’s Neil McCauley are the central relationship of the film. They mirror each others’ strive for excellence in their given profession, they both desire meaningful relationships with their coworkers, friends and family, and they both historically have trouble managing them. Vincent is three marriages into his life and he’s still being accused of not being present enough in the relationship due to the hours his job demands. For Neil, the constant threat of being caught by law enforcement for being a master thief has been his excuse for not creating relationships outside of his robbery crew members. As their paths become more intertwined as the movie progresses, the more they recognize and respect each other’s methodology and tactics.

Their mirror of self-reflection is held up most prominently during the infamous diner scene. One night whilst surveilling Neil, Vincent decides to break protocol and take him for a late night cup of coffee, in which the two cautiously reveal their true nature to one another. What they find is more in common than one might expect, including the fact that their line of work makes it difficult for them to connect with others who exist on the outskirts of it. Despite how much these two men share, the most important thing they differ on is who they value most in their lives. The pair discuss a hypothetical stand off between the two during the commission of a crime by Neil, and reveal to each other how they would view the conflict. Neil’s concern is his own self-preservation by framing it as a choice between killing Vincent and going back to prison. Vincent frames it as a choice between saving a wife from becoming a widow and allowing a man to die because of Neil. What their respective subconsciouses are telling the audience is that Vincent values the collateral damage that Neil has no regard for.

The dramatic tension at the core of both men is tied directly to their self-awareness. Neil starts the film as being more honest with himself and gradually becomes more consumed by the ego of his work. When his newfound love interest, Eady (Amy Brenneman) is introduced early on in the film, the script brings in a symbol for his redemption. With Eady, he could fulfill the classic trope of leaving criminality behind and starting anew. What unfolds throughout the film is this delusion swallowing him whole, and taking him to a place where he chases revenge instead of his fantasy. He becomes the victim of his self-deception, whereas Vincent starts the film in that place. He believes his entire value as a man is his line of work, and that his personal life must be a distant second to chasing the hardest criminals in Los Angeles.

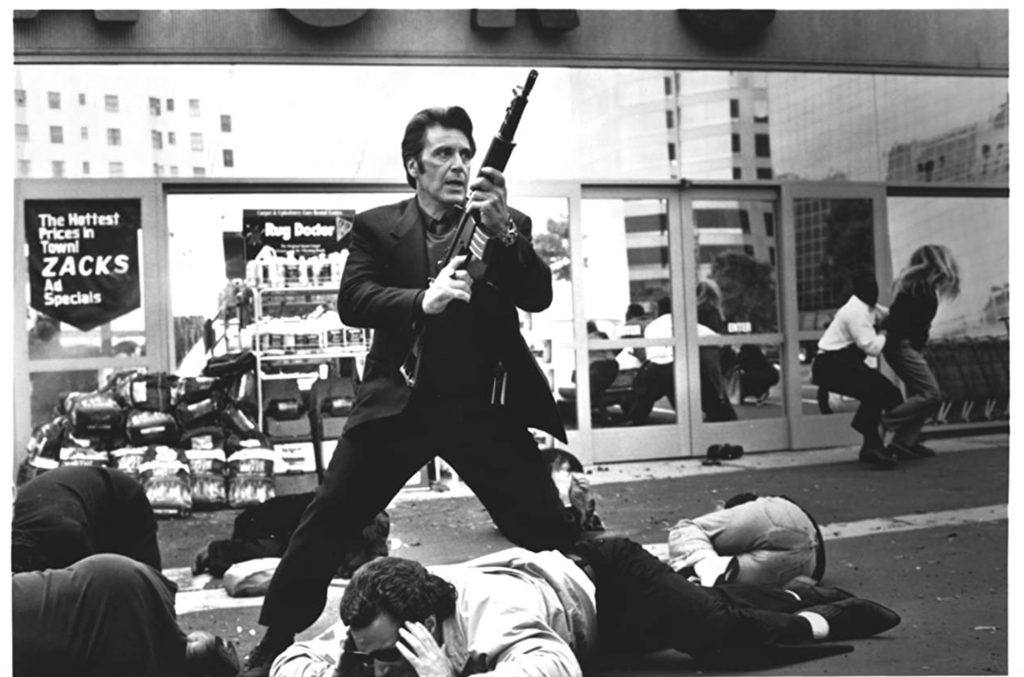

There are hints of Vincent’s transformation throughout the film, such as his overwhelming kindness towards his step daughter, played by a young Nathalie Portman, or his compassion towards a mother who is at the crime scene for her own teenage daughter. It’s very telling that Mann chooses to have Vincent’s arc revolve around his ability to save children from the cruel horrors of the world. In the infamous and masterful shootout sequence, Vincent ends the fight by striking a headshot onto the robber, Michael (Tom Sizemore) after he takes a young child hostage in order to fend off the police. Vincent’s self-deception is that he believes he is designed to take on people who are the best at what they do. The best thieves, the best serial killers, the best evils that the world can throw at him. Vincent’s interactions with family and children throughout the film are, unbeknownst to him, thawing out his cold heart.

When you re-examine the arcs of Neil and Vincent based upon their personal journeys, then there is a layer of optimism that exists beneath the surface of the film’s ending. Their climactic showdown takes place at night in a secluded area of LAX’s tarmac. This cat and mouse game concludes when Neil tries to ambush Vincent when he’s facing the other direction. When the lights of a plane taking off reveals a moving shadow at Vincent’s feet, he quickly registers that to be Neil and turns to take the kill shot. Vincent literally “sees the light,” and as Neil bleeds out he extends his hand, hoping for some show of compassion. Ultimately Vincent does, signifying the completion of his transformation. If he can show his truest enemy this kind of heart, then perhaps he will finally show it to his family. Perhaps now that Vincent has finally beaten the best, he can finally stop being a police detective and start being a husband and a father. Perhaps now he will allow himself to enjoy his relationships in life, rather than feel hindered by them.

As Moby’s music creeps in while Vincent looks on into the night, the sense of completion and fulfillment washes over the audience in the most simple but memorable way. There is a reason this film is looked back on as a classic; it taps into a level of humanity that only the most sentimental of auteurs can express. Genre-filmmaking is meant to trojan horse ideas into entertainment, and the fact that Michael Mann got close to $100 million to make a relationship drama, disguised as an action film, is astounding by today’s standards. Many have tried to replicate or emulate Mann’s work here, but few will ever come close to reaching the audience the way Heat has.

Comments