Denial During a Crisis: The Big Short

As proclaimed by the King James edition of the Bible: “pride goeth before destruction and a haughty spirit before a fall.” Plenty of people fell victim to this attitude during the 2007-2009 crash due to the US housing market’s collapse. And how could you not have? All of the financial experts claimed the it was the safest place for your money, every business news outlet backed up these claims, the so-called “independent” ratings agencies rated investment grade, and the government gave them all the federal stamp of approval. In 2010, Michael Lewis (of Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game fame) published The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, and in 2015, Adam McKay brought us an uncompromising look at how the seemingly impossible became possible.

Herd mentality is the theory that people will adopt the behaviors of those around them, even if said behavior is in direct contradiction to one’s own instincts or well being. Our main characters in the film live their lives outside of the proverbial herd, and for them it is a point of pride. The different factions of the cast don’t all intersect, but they all come to the same conclusion: the mortgage-backed security market is destined for collapse due to owners/tenants defaulting on their monthly payments, and this fact is being hidden by the ratings agencies and banks who own this debt who ultimately succumb to the moral hazard of the federal government’s backstop of the loans.

As explained by Ryan Gosling’s character, Jared Vennett (based on real-life Greg Lippmann), the financial industry likes to use complicated terminology to discourage understanding and scrutiny from the general public. However, the film makes it its mission to de-mystify the intricacies of the market and uses various techniques to break the fourth wall with the audience, and explain things in an entertaining and humorous manner. The tight rope act of the film is not to allow these explanations to become condescending or smug, and just before the film ever reaches this point, it switches tactics and plays things straight. The tonal balance between comedy and tragedy can only work in the hands of a master, and Adam McKay proves himself to be a deft orchestrator of the audience’s emotions.

Adam McKay made a name for himself as an early 2000’s staff writer for Saturday Night Live, and then making Will Ferrell a movie star by directing him in Anchorman (2004), Talladega Nights (2006) and Step Brothers (2008). In 2010, he directed Farrell again in The Other Guys, a buddy-cop comedy that featured a villainous plot behind a Ponzi scheme preying on the NYC police pension fund, and an ending credits graphic even detailing how a Ponzi scheme works. Needless to say, it seems that McKay now has a dog in the fight of modern financial crimes. His interest in the subject, as well as his resentment for the victimizing of the American public, comes through in his first foray into dramatic filmmaking.

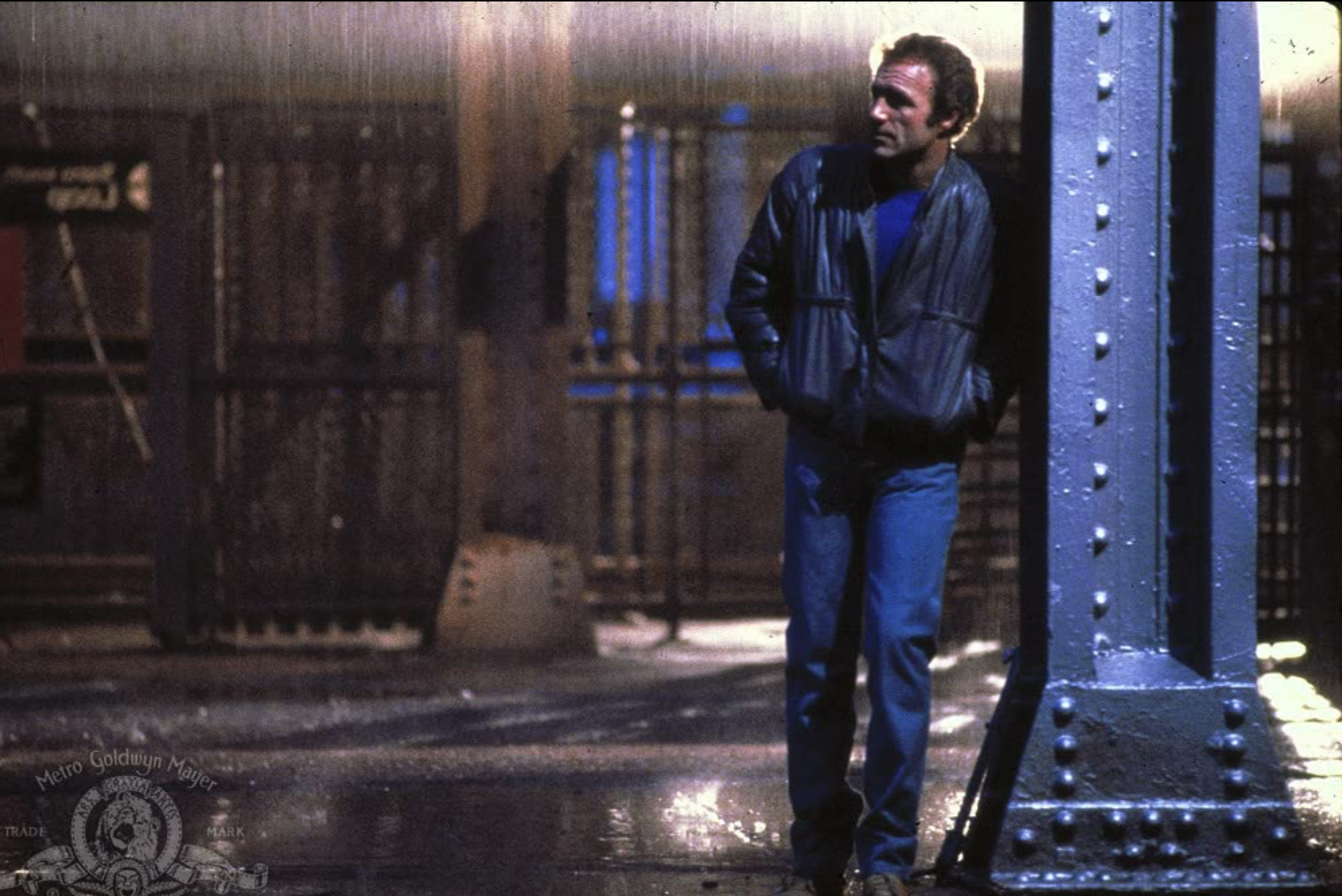

In order to keep the film from devolving into total nihilism, Steve Carrell’s Mark Baum (based on Steve Eisman) and Brad Pitt’s Ben Rickert (in real-life, Ben Hockett) provide us the moral conscience of the film. They both lament the corrupt underbelly of the financial system and as we see in the film, they both come to the conclusion to leave it all behind once they take part in their fair share of morally-onerous activity by betting on the collapse. When two other characters are celebrating their likelihood at winning big on their bet against the market, Rickert stops them and reminds us that the loss of jobs, homes and livelihoods is not something you want bragging rights over.

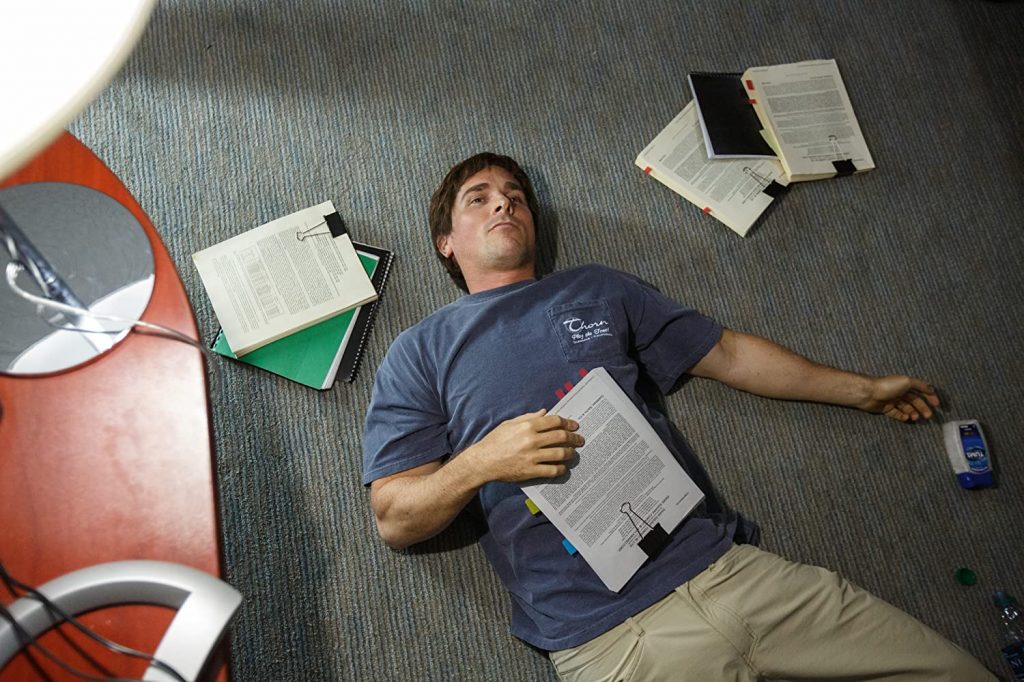

The first person to quantify the possibility of the markets failure is California hedge fund manager, Dr. Michael Burry, played by Christian Bale in his usual brand of subtle and potent transformation. Burry is the dictionary definition of the term “outsider,” and is a man who lives an honest and socially awkward existence. He crunches the numbers, and if they don’t tell a reassuring story, he is not going to make them sound like they do. When his investors see how he invests their money in his short against the market, they all point to their own “trusted” sources in the mainstream culture as the reason Burry has lost his mind. Since we as the audience have 20/20 hindsight as to how events ended up, we know Burry was right from the start.

The film does not just ask the audience to take the lead characters at their word, it rightfully shows Mark Baum’s employees put their boots on the ground at some of the properties with unpaid mortgages, speak to the realtors who sold the homes, and then finally an executive at the Standard and Poor’s rating agency (Melissa Leo). Mark learns from this executive that there is a belief that trickled down to the consumer from the federal government much more sinister than ignorant negligence: the banks will give their business to competing credit rating agencies if S&P does not rate their securities AAA (the highest rating). This practice has been commonplace for decades, and it forces Mark to the conclusion that if banks are meant to be regulated and such federal agencies allow the practice to go on, then they must be complicit in the duplicity.

The role that herd mentality takes in a circumstance like any financial collapse, is the belief that if things have been going well, they will continue to. In short, denial is the disease that infected the world of debt. There’s a particularly poignant montage of pop culture events, early on in the film that highlights how denial is allowed to manifest. There are flashes of every significant celebrity, film, music video, sporting event, etc. that occurred whilst the housing market slowly crumbled, highlighting how easy it is to be distracted from the statistical realities that lie beneath it all. This leads into another great strength of the film: not punishing the viewer for taking part in pop culture.

Adam McKay wanted you to enjoy his films in the early 2000’s, and he wants you to get something out of this one, too. The film is not interested in slapping the audience on the wrist for giving his work viewership while the economy experienced hardship. The moral slap on the wrist exists for the institutional corruption and the arrogance of the banks and money managers who follow the official narrative, and deny the root cause of any troublesome activity. One of our personified lens’ into this thinking is Tracey Letts’ character; an investor in Dr. Burry’s fund who thinks that Michael never should have used the fund to bet on an “unlikely” catastrophe. We see this brand of ego today, as expressed by those who think there cannot be any long term consequences to anything as unprecedented as shutting down the world’s economy for any extended period of time.

The people who get left behind by the previous collapse, and who will also face hardship in our current predicament, are the small business owners and heritage brands that believe in economic freedom and simply want to sustain their employees and provide for their customers. Most people agree that this is all a tragic by-product, however the subject that mainstream business outlets will not touch is how this upcoming economic hardship is not simply the reaction to a pandemic-related shutdown. The kind of debt crisis that our current economic state will lead to is not a reactionary occurrence, it requires decades of malfeasance in order to manifest. Once again, The Big Short exemplifies its comprehension of historical precedent and goes over the banking “innovations” that set the stage for a future disaster.

The ending of the film warns us that this can happen all over again if we sink back into a state of denial, and do not engage in educated risk management. Over the coming months we will provide a set of films that are worthy of your consideration as this crisis unfolds. Films such as Wag the Dog and Trillion Dollar Bet are required viewing as they provide deep insights into the perilous world in which we are entering. On our companion site, Reagan.com, numerous blogs and book reports will help equip you and your family with considerable and often conflicting viewpoints (from the mainstream) that could be essential to your decision making – especially in financial matters.

Comments