Attempting Free Enterprise: Thief

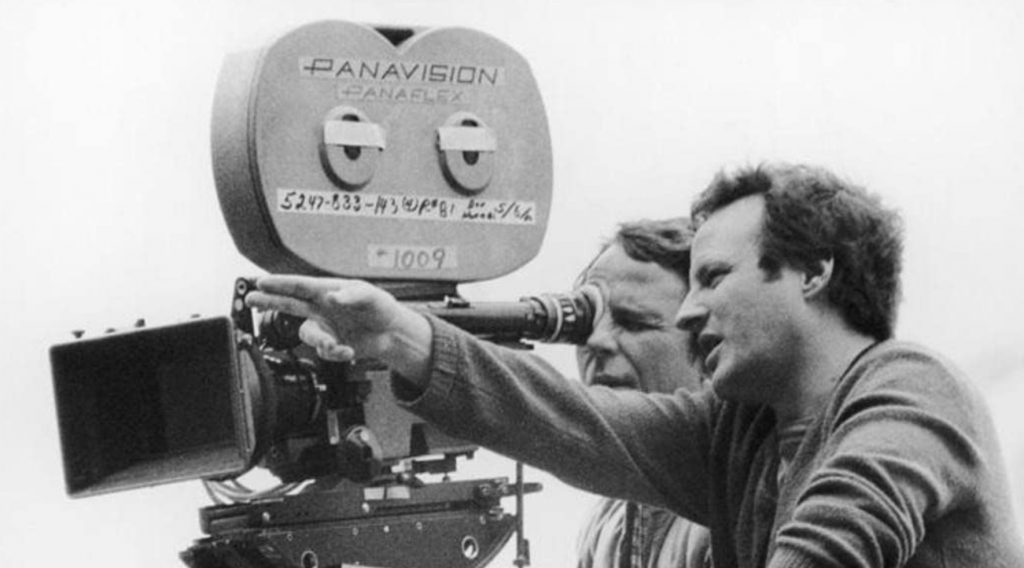

Imagine what being in prison for a decade takes away from a person. Start with the immediate things such as time, opportunities and freedom of choice. Then think about what passes you by, such as technology and culture. It’s only natural for a person to feel lonely and irrelevant when they realize how much of the world has passed. Enter Thief, Michael Mann’s theatrical debut from 1981. The ground work for every theme Mann would later explore is present in the DNA of this film, but no other film of his felt as personal as this one.

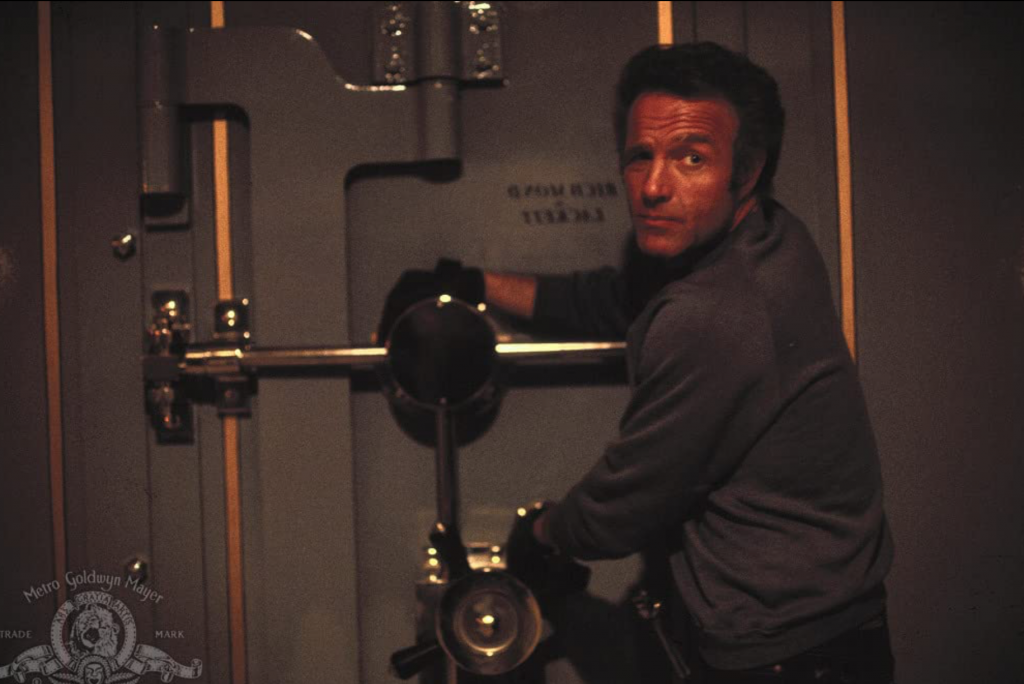

Frank (James Caan) is the best at what he does, which happens to be cracking safes and stealing. He’s fresh out of prison for an 11 year sentence for theft, and he’s back at it again in the opening scene in the movie. He’s in a rush to make up for lost time and resources, and the only way he can narrow the gap is by going back to crime. His initial conviction was for the theft of $40 but because he defended himself on the prison yard, that conviction went from a small amount of time, to a third of his life thus far. He’s in a hurry to move on, understandably so, but he’s got to play catch up with the world around him. He doesn’t have time to waste on being polite or patient. He wants what he wants, and he needs it now.

The woman he wants is Jessie (Tuesday Weld), and he wants to commit. During a late night coffee date with Frank and Jessie, he lays out his plan for the rest of his life to her. He wants a home, a wife, a child and all of the things he felt were stolen from him. The romance between the two is real, and this exchange is easily the stand out scene from the movie. Frank’s impatience to restart his life is almost childlike, but his honesty and vulnerability draws the two together. Despite the tough guy energy he developed in prison, Frank is devoid of ego. He has no patience for deceit or a double life, he wants one life and that it be his choice of life.

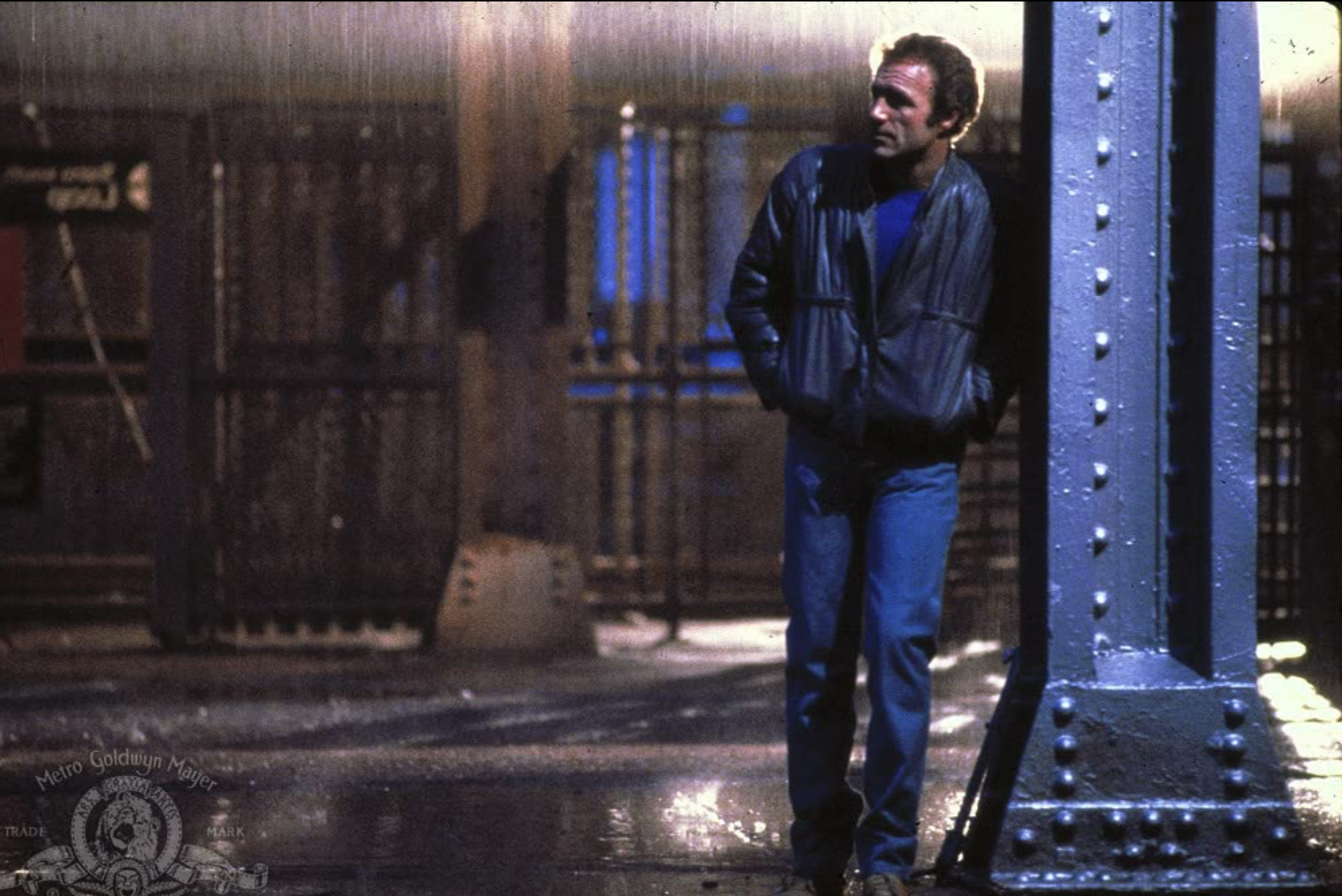

Frank’s agency is challenged by the Chicago mobsters who contract him for one final heist. The take-home pay for this job could set Frank free but because this is a crime thriller, none of it ends up being that simple. The thing that creates friction between him and Jessie’s ride off into the sunset throughout the film are the institutions that want their pound of flesh and labor from Frank. The mob, corrupt police officers and even state-run orphanages when the two attempt to adopt a child. At every turn, there’s a large entity preventing Frank from putting a period on his criminal life.

The parallel we’re drawing is obvious, large entities will always want people to play by their rules and they will keep moving the goalpost until they get everything they can out of you. Frank was state-raised in the foster care system; a place said to give abandoned children a chance at success in life, but statistically prolongs their neglect and abuse. He was set up for a life of crime, but thankfully chose the nonviolent route of petty theft. $40 got him convicted at 20 years old and doomed him to defend himself from attempted rape and murder by the other inmates. When he successfully fended them off, his sentence was extended. The prison system claims to be a chance at rehabilitation for criminals, but it often punishes them further when they stand up for that very chance.

There’s a comment in here about how surviving a self-defense situation only puts you in deeper water with the government/courts, but it’s doubtful that was a flourish by Mann. More likely is that this is an example of 2021 vision drawing parallels to today from Frank’s misfortunes. That being said, it does not make the comparison any less pertinent. Frank has been facing physical and systemic threats his entire life. Even now as a free man, in the law’s eyes, he is being prevented from moving forwards in his life. His prison time will prevent him from seeking real employment opportunities, as well as adopt a child from the same kind of facility he grew up in.

While Frank faces road blocks on his Pursuit of Happiness, he also must contend with the corrupt entities who have threatened his literal life and the life of Jessie. They know what Frank is worth as a thief, which is to say he is the best man for every job they have. A man like him cannot be allowed to retire, he’s their milk cow. When Frank is meant to be compensated for a job by Leo, the mob boss he is indebted to (Robert Prosky), he is told that his payment has been invested into “shopping centers” as opposed to cash. Leo also arranges a follow-up job to the “one last job” that Frank has completed. Once again, the parallel to the present is clear: a controlling entity keeps moving the goalpost for an individual’s freedom.

Although Frank never has the awareness of the ideological battle at play between his freedom and the underworld’s restrictions, his survival instincts kick in as the walls close in on him. What we see in Frank’s descent into the underground economy throughout the film, is that it is impossible to outrun corruption by playing by the rules. When those in charge keep changing definitions behind the rule of law, then are there truly any rules? How do you be a law abiding citizen when no matter how ethical you are, the “lawmakers” hold you hostage for your decisions?

Is the audience meant to employ the same tactics as Frank in order to get ourselves out of oppression? Not necessarily. Frank is a part of an overtly lawless world and his desperation is being dramatized for entertainment purposes. However, is there a parallel between criminal factions and the federal government encroaching on the very idea of independence? Yes, and a very clear one. The takeaway is that if you succumb to the circumstances that Frank faced in his upbringing, you will be forever indebted to those who created those circumstances. When the government catches you in a moment of weakness (a moment all people face in their lives’), they will hold you hostage by it.

The advantage that most people have that Frank didn’t, is that most people have been educated as to what a higher moral standard looks like. Whether or not we all strive for it is a different story, but for the most part there is an awareness of what an honest life looks like. Frank is caught in the unfortunate position of making up for lost time with his decision making. For those of us that have been saved of his troubles in the criminal justice system, the decision making must be impeccable. Our lives and livelihoods are scrutinized to an unfair degree when we defend ourselves and our free enterprise. The higher moral standard and often playing by their rules are not just an emotional goal for our relationships, it’s the only thing that can protect us.

Comments