Walking the Righteous Path: The Equalizer Series

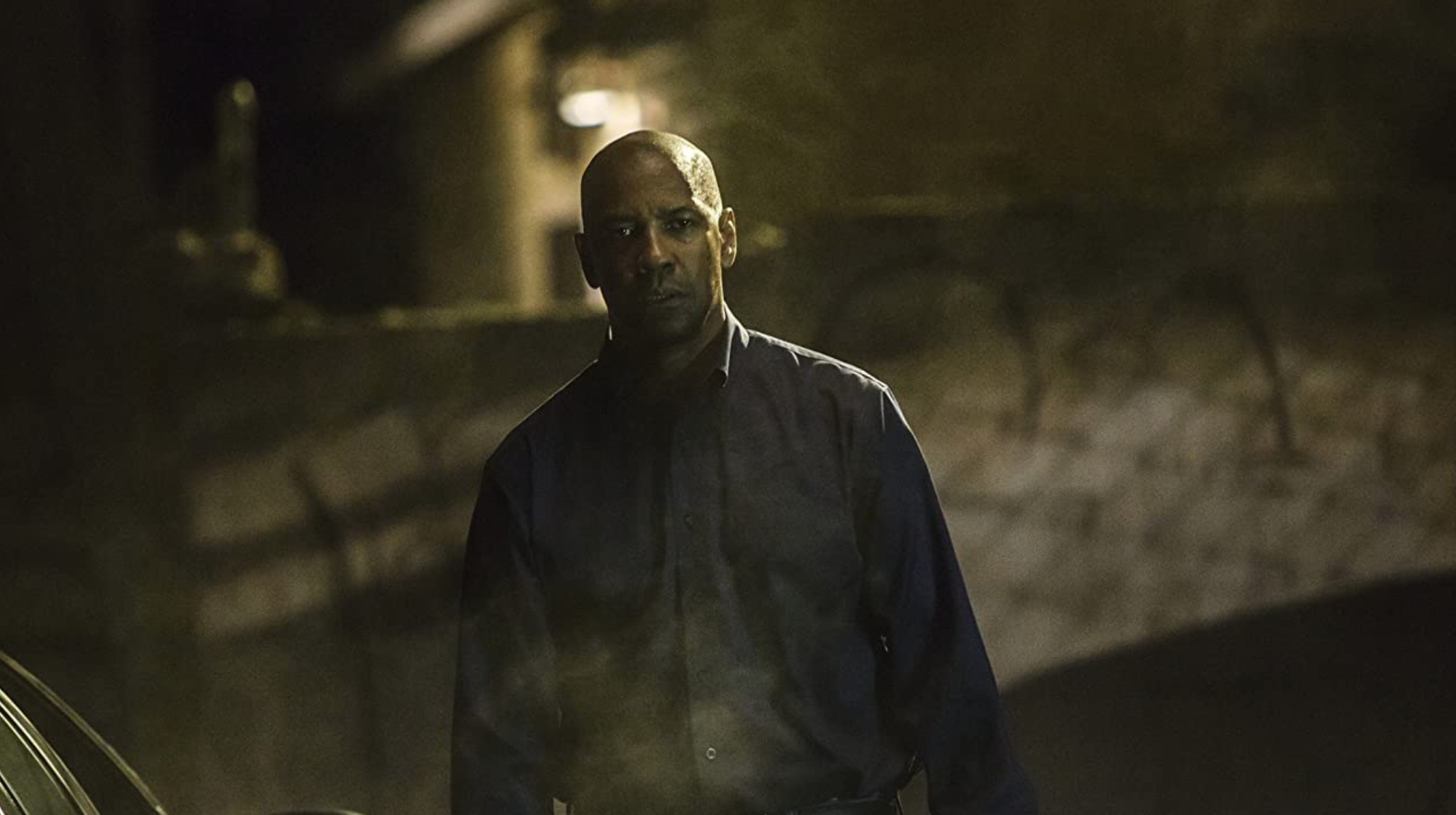

“What do you see when you look at me?” This question is on the surface of Denzel Washington’s The Equalizer films as a source of intimidation for his adversaries. However, the meaning beneath these words resonates as an existential challenge posed to the evil-doers receiving them, the man who delivers the words and the people in the audience bearing witness to it all. Cinema and the surrounding culture talk a great deal about taking action against injustice, and when it’s dramatized in the form of action cinema where death is dealt out to morally bankrupt individuals, it’s easy for us to hear the sentiment without translating it into non lethal behaviors in our own civilian lives’. It’s about time that the aforementioned translation from art to life be done, and that we illustrate what righting the wrongs of the world looks like at a local level.

Movie stars producing their own franchises is usually done as a means of both job security and ensuring they always have a creative outlet for their passions. Look at Ryan Reynolds’ with the Deadpool series, Tom Cruise with Mission: Impossible, or Keanu Reeves with John Wick. There is a unifying vision, tone and quality across different iterations of these series’. This is partly due to the fact that the creative teams are calling the shots, not the studio mandating these films be made. The other benefit of working like this is that these A-listers get to imbue their work with what they value about the world and cinema into each iteration of their work. With Denzel Washington, there are a few career checkpoints where we can see his belief about the world come through in his choice of projects. Between The Book of Eli (2010), Flight (2012), Fences (2016), Roman J. Israel, Esq. (2017) and the two Equalizer’s (2014 and 2018), we start to see a pattern of characters whom strive to lead a life with higher purpose and a firm code of ethics, only to be pressured by society into breaking said code.

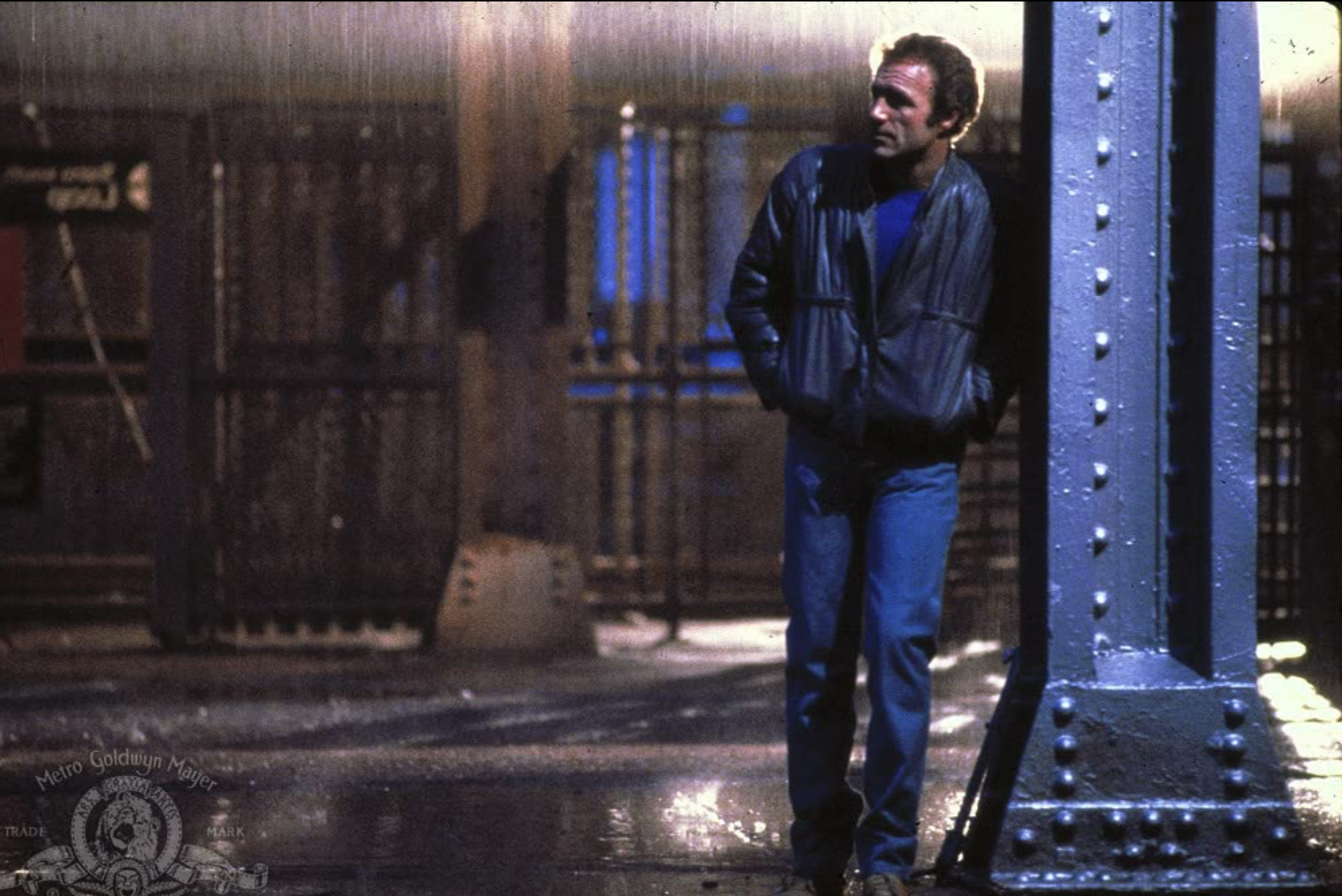

In The Equalizer films (based upon the 80’s television show), Washington plays Robert McCall who is a retired special operative living the quiet life in Boston. His routines are immaculately timed and executed, and his work ethic at his “everyman” work places are equally as proficient. It’s a minimalist life that seemingly exists in a world outside of modern frivolities and harkens back to the GI Generation. Robert gave his service to his country and now indulges in the very comforts and opportunities that he fought for. Just as America has technologically advanced, so has the methodology of war and service. Where once there was a historical dignity in armed combat by looking the enemy in the eye, it has since become one of moral destitution and obfuscation with intelligence and psychological operations. Bringing an end to the enemy meant the assassination of their character in addition to their actual life. McCall was a part of this transition, and its clear that this change wore on his conscience, despite his exceptional skill at it.

It’s here that we find the classic Denzel Washington-archetype. He exudes a fortified and moral presence with every inch of his being, only to be called to break his own rules when that morality is challenged. In this series, Robert’s various co-workers, neighbors and friends are victims of injustice of varying levels of financial trauma and more importantly, physical violence. Even though his own quiet life has not been challenged, and by law has no right to insert himself into their situations, his personhood will simply not allow for these criminals to go without punishment. As understandable and even enviable his drive to level the playing field for the commonwealth is, it is an act of ego for him to step outside of his world in order to help someone improve theirs. Ego may carry a negative connotation in today’s vernacular, but if selfish energy is sent towards a selfless purpose, do we have the right to condemn it? If anything is done for the right reason, can we truly fault the behavior? Sometimes yes, sometimes no.

In the case of Robert McCall, the argument is made well enough that he is a righteous man, but the question posed by this series is “How righteous can a man be if he takes a life of another?” In the second film, we see Robert take a young man under his wing named Miles. Miles is a talented artist and painter, but he has been led to believe by his socio-economic status that his gifts will not provide for his own or his mother’s livelihoods. A local gang attempts to initiate Miles into their world of murder, theft and depravity. When Robert saves him from this fate, he instills into Miles that only he can decide to live righteously and if he has talent for something then it is his purpose to use them, no matter what anybody says. It’s in this scene and dialogue where we can draw comparison to the Christian faith. McCall is a messiah-like figure who walks a path to paying the moral debt brought on by sin and iniquity. The difference being it is not Robert’s own life that is sacrificed in exchange for the commitment of sin, but it is his soul that is given to “equalize.” He has sacrificed his own redemption for years of combat and killing so that his friends and neighbors may walk their own enlightened path.

All of this being said, the question still stands as to what we as the audience are supposed to take from these pieces of entertainment? Are we morally obligated to sacrifice our own comfort and virtue for those around us? As referenced in 1 Samuel, 15:22, then obedience and the ability to listen is preferred over sacrifice (at least in the literal sense). Different theologies and beliefs subscribe to varying levels of pre-determinism, and even within the various sects of Christianity there is plenty of debate, still. For the sake of this analysis, we will set aside the debate about how in control of our individual destinies we are. For now, let us ask this: If your own path has crossed with another person’s, and you have the opportunity to help them, then is it your job to do so? There is no easy answer to this, and this level of engagement and high-level thought is not encouraged in the current era.

Digitizing social interaction, collectivism and “silence is violence” rhetoric are all various tactics that manipulate people into being outwardly supportive of large swaths of the population, but by now we have figured out that these beliefs create no behavior to help. If anything, they allow people to disconnect from each other. Neighbor’s aren’t interacting on their driveways, parents aren’t connecting whilst picking up their kids from school, professionals aren’t networking at large conferences. Everyone is encouraged, forced and even demoralized to be at home on their computer. From here we are conditioned to engage in talk of the “greater good” and “saving lives’ by staying home,” when we’ve never even met these people. How many of us give birthday cards to our coworkers, or even send a “Merry Christmas” text to our extended family? You’re not uncaring if you don’t but if we can acknowledge that reality, then how can we possibly expect to provide a service to global needs when we lack the mastery of fulfilling local ones? This is the emptiness behind a politicians’ rhetoric. How can they possibly care and act in service of people whom they have never met, when we as individuals barely have enough time for everyone we know personally? 24 hours a day isn’t a very long time, and even over the course of a month we can’t possibly reach and effectively help everyone we know or care for.

There was a period of time in America where we cared about the struggles of those around us, and in large portions of the population that still exists. The unfortunate thing is that these are not the people we hold up as heroes anymore, and is it because our values have shifted given the rise of structural and societal evolution? Or is the blame also shared by cultural drivers of national conversation? Maybe the blame goes back to the public for allowing this deterioration of ethics to happen? The truth is a fascinating dichotomy, as it is both all of those factors and none of them. Things always go wrong when we try to step outside of our skillsets and beliefs into an industrial world that we have no understanding of, or instinct to navigate through. This is a different concept from stepping outside of our comfort zone in order to expand our minds. The former prevents us from providing aid to others, and the latter equips us to do so.

When Robert McCall heard the call for help, he knew he had the skillset to answer it. Too many of us let ourselves off the hook from decency if we perceive that we have nothing to offer a situation. Did we know there was nothing we could do for certain, or were we looking for an excuse to not care? If we did our due diligence and offered help to someone who seemingly needed it, and our gesture was turned down, then we can certainly say that we were not called to help them. The extra time it takes us to take this kind of consideration to heart is seen as an inconvenience, and that’s partly because it is. However, it is our job to distinguish whether this is an example of sacrifice or obedience of the path we all walk.

Depending on how you interpret Robert McCall’s view of his path, you may see The Equalizer films as a tragic sacrifice or a reaffirmation of obedience. As we posited earlier, does Robert choose to sacrifice his own virtue for the good of the people he cares for? Or is it actually that he has been called to bring justice to the people who elude it? The purpose of this discussion is not to advocate for or against the death of a human being, no matter how evil their actions. The purpose here is to ask ourselves what we can do to create the better world we all talk about. The answer is given to us early on in the first film when Robert tells a teenaged prostitute: “Change your world.” Whose journey did yours intersect with? What do they need help with? Do you have the ability to help them? If not, do you know someone who can? This concept will most likely seem obvious, but if every American were living this belief, would we be facing this scale of ideological divide?

The reason we find ourselves in this moment is due to the fact that we are no longer living in the present moment. Our self-awareness and confidence to act upon our ethics is at an all-time low. We stopped desiring to be neighborly, and examples for us to reference this behavior became harder to find. We used to look to the press, the church and the movies for this kind of teaching, but we either can’t trust them or can’t even go to witness them. The desire to deliver hope to others has been co-opted or outlawed entirely. The answer to our national dissonance is not going to be as easy or superficial as a piece of legislation, a medical advance, or even a political race. It is a far more difficult and deeper behavior to be neighborly and attentive of those we meet along our own paths, but it is the only thing that preserves our spirit of freedom, just as the very concept of being free is challenged.

Comments