Enduring an Upset Establishment: The Dark Knight Trilogy

“What would you have me do, Alfred?”

“Endure, Master Wayne.”

The cinematic legacy of Batman can be summarized by this exchange in 2008’s The Dark Knight. The Batman mythos is as elastic and withstanding an intellectual property as any other work of great fiction. Audiences are willing to accept Batman in all manner of ways. The cheap laughs and quirk of the 60’s television show, the neo-noir gothic world of Tim Burton, the hyper-sexualized campiness of Joel Schumacher (say what you want, but it made money), the retro grit of the Bruce Timm and Paul Dini animated series; they were all viewed with open minds and hearts. However, none became part of the monoculture like Christopher Nolan’s idea to bring Batman into our world, and force him to figure out his place in it. By the time The Dark Knight had finished its theatrical run, it became the event film of the century with its legacy rising far above its shortcomings. People stuck with this journey to completion, and its effect on the art form are still felt to this day. Reflecting on these three films cannot help but make you realize how much of a miracle it is that they turned out the way they did. The delicious paradox of their legacy: that these were films about a crumbling establishment, made in cooperation with the real world embodiment of those same structures. A society on the brink of turning on itself, and the one symbol of morality that could rise from within the decay, and reach heights that we did not know were possible.

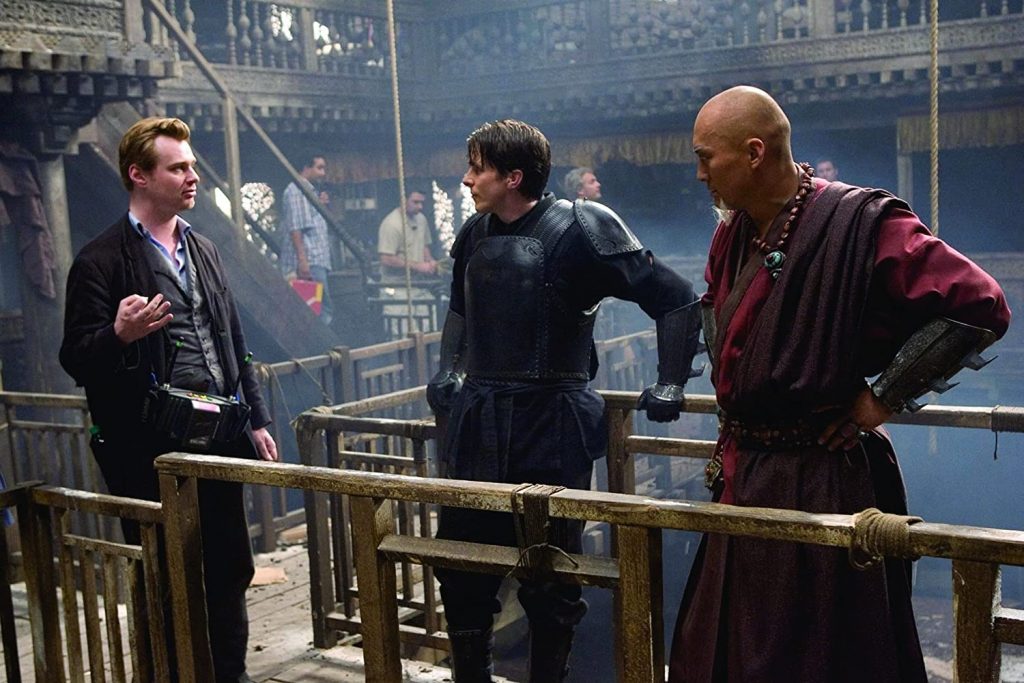

The Batman intellectual property was on ice (no Arnold pun intended) following its 1997 iteration, and when Warner Brothers was looking for a way to revive it, then-rising director Christopher Nolan won the job. His pitch of grounding Batman in modern America and having the character earn his iconography throughout the reboot was extremely enticing because it was the only place untouched by the character’s previous film forays. Stripping the trappings of the Batman lore down to the core psychology of what made it the Detective Comics centerpiece only made sense, given Nolan’s filmography up to this point. Following his inaugural film, Following (1998, pun intended), he made Memento (2000)and Insomnia (2002). The blueprint for his style of Batman exists in those films: psychological thrillers with A-list talent that got the most bang out of their budgetary buck. Everything he promised to the studios with those films were delivered on time, without deviation, without any behind the scenes drama. Nolan had the temperament and expertise to handle the bigger price tag that comes with a valuable intellectual property and not let ego come into the equation. Batman Begins debuted in 2005 to critical acclaim, box office success, and widespread audience approval from fans and non-fans alike. Everything he promised the film would be, it was in spades. Nolan has since cultivated a career of fulfilling every promise he makes to the audience. While he still has plenty of detractors, no other director working today can sell a movie on their name alone.

One of the many things that has made these films age so well, is the amount of meaning that can be retroactively placed on the film. Nolan’s focus on narrative allows history to rest itself on top of the film. Many complain that his films age out as glorified “proof-of-concepts;” films that show he has the technique, but not the wherewithal to flesh out his high-brow ideas. Whilst there is some truth to that, I would argue that the modesty of his filmmaking overshadows this statement. He is a filmmaker that believes the audience to be smarter than him, and thus respects our intellect and imagination even when his exposition and narratives start to cave in on themselves (the Lau/Hong Kong subplot in The Dark Knight has no business being in the movie, but somehow WB let him get away with it, so keep shining, Chris). How this translates into this trilogy is his focus on examining how Bruce Wayne is forced to adapt his ideology to the changing attitudes of the people of Gotham.

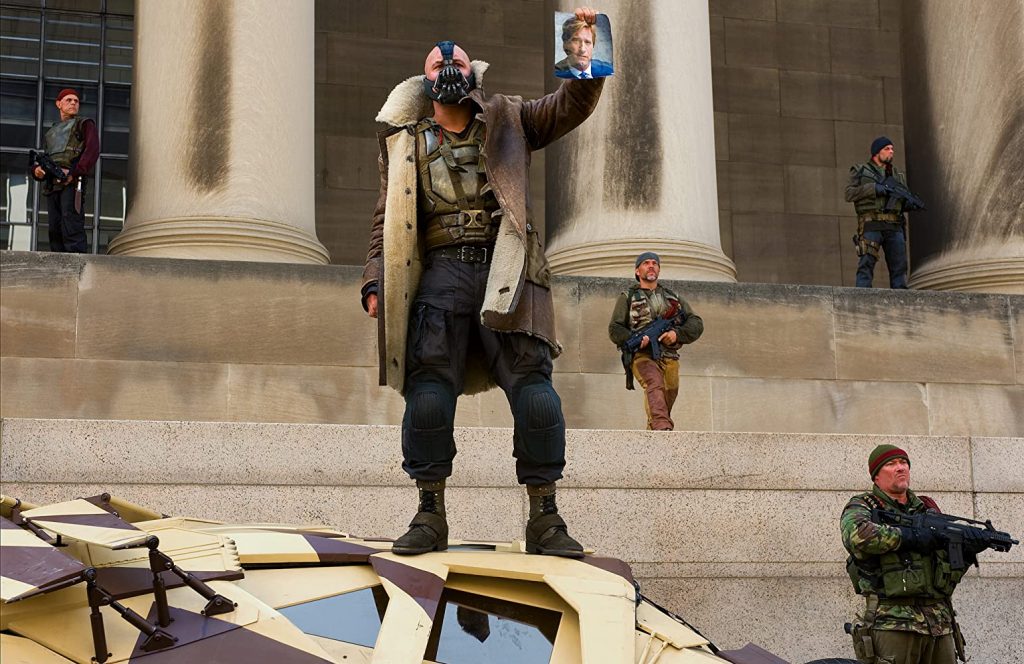

In Batman Begins, the city’s infrastructure is so tainted by corruption and duplicity, that Bruce Wayne can only the right these wrongs outside of the justice system. The villain’s plan (Liam Neeson as Ra’s al Ghul, hot take: favorite villain of the franchise) is to use a fear-inducing chemical to turn Gotham’s people against each other and allow the city to develop anew on top of the bodies of the current generation. In The Dark Knight, the Joker (the legendary Heath Ledger) means to incite chaos amongst the populace in both randomized and calculated moral puzzles. In The Dark Knight Rises, Bane (Tom “behind another mask” Hardy) seeks to fulfill Ra’s al Ghul’s mission to impress their shared organizations’ values on the city, by inspiring a pseudo-revolution and isolating it from the nation as a failed state under martial law. The pattern here is that the only true means of destroying an ideal is by challenging the belief behind it. Batman’s power as an icon is that he represents a means of empowering the disenfranchised masses, by channeling anger and distrust into palpable change. The only means of stopping Batman is to expose him to be the very thing he claims to combat. All three of these villains seek to undermine this iconography in very different ways, albeit working towards a smilier end. What’s impressive is that these films are still so unique within their individual installments, despite recognizing this repetition.

What ties these films together is Bruce’s relationship to the people of the city. In the first film, Nolan establishes how Bruce has inherited his father’s compassionate spirit. His wealth is used to provide a comfortable life for his family, as well as improve the infrastructure of Gotham so that his fellow citizens may also reap the benefits of capitalism. Bruce’s decision to create the Batman persona is his way of continuing the Wayne legacy, and in a (twisted) way it does. What unfolds in the following two installments is how he both inspires good intentions in the common man and woman of Gotham, as well as the competition of his enemies. The Joker’s pathological lust for unrest inspires him to unify and manipulate the desperate remains of organized criminals. Bane’s penchant for martyrdom drives him to use the wealth disparity of Gotham’s citizens to divide and conquer. He isolates the police force, inspires the entitled to “de-throne” the one percent, and leaves the under privileged in the wind as a hypocritical result.

It is impossible for Nolan’s conception of the modern Batman myth to exist anywhere but in a post-9/11 America. The idea that Batman must use sonar technology to monitor every cell phone in Gotham to find the Joker, is about as close to a film about the Patriot Act as we have gotten. If you’re going to set a story in the modern age, the modern age is implicitly going to find its way in. Nolan is concerned with allowing the audience to put their own meaning on top of his films. To Nolan, the imagination is the most sacred place in the mind (even being on record for hoping the ability to read minds never comes to fruition). Nolan’s writing covers this base by using the Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman) character to protect this belief, and has him challenge the methods Batman employs to stop this great threat. The idea of sacrificing the privacy of Gotham’s citizens in order to stop the threat of the Joker’s domestic terrorism, is a question Nolan asks and purposefully does not answer. It’s up to us to decide if he is right to do so, and if the Joker’s capture still warrants this compromise.

The coincidence that Bane calls for violence against the one percent, whilst The Dark Knight Rises was filming mere blocks away from the Occupy Wall Street movement is the kind of rich irony that would feel contrived if it were not real. I use the term coincidence because it is just that. The idea that Nolan was being opportunistic of a movement that did not exist when he was making the schedule for the 2011 shoot is ridiculous. The retroactive intrigue of this plot point is that Bane is exposing Batman to be a false idol for hope, when that is what Bane actually is (given that he plans on nuking the city). In order to prevent this, Batman must lead a resistance made up of the liberated police force and a supporting cast pulled from an Oscar-Nominee “Bingo card.” I doubt many other filmmakers would even entertain the notion that the one percent would be the only entity that could create peace, so kudos to Nolan for not being so overt and also not backing down.

The artistry and consistency on display throughout the trilogy is what solidifies its place in history. Only the best actors for the roles have been cast in front of the camera, and all of them provide A-game material. Nolan experiments with practical techniques to photograph some of the most jaw-dropping action sequences the art form has ever provided. His behind the scenes crew stuck around for all three films, and the audience is the beneficiary of this loyalty. These films make it easy for us to reciprocate this loyalty, and if Nolan’s non-IP endeavors have proved anything, it’s that we don’t care what his film is about, we will go and see it. When we discuss the concept of a Reel Values film, we talk about a creative team that respects the audiences’ time and energy, and a film whose meaning and quality ages with them. Nolan’s filmography is built on this criteria, and even this discussion of his Batman trilogy has barely scratched the surface of what these films have to offer the viewer. The endurance of his ethics as a filmmaker is what made him so compatible for the Batman series.

The upcoming reboot with Matt Reeves in the helm could not be a better follow-up to Nolan’s vision. His recent Planet of the Apes films were made with a similar sensibility; taking time between installments, allowing the audience to react and develop their expectations for the franchise, and then allowing the films to be inspired by a new story to tell in the world they’ve created. However, what really sets these two franchises apart from the rest is knowing when to walk away. The Dark Knight Trilogy and the recent Planet of the Apes trilogy have a definitive beginning, middle, and end. Whilst Warner Brothers is rebooting these two franchises, it is quite refreshing to see that they are allowing the new filmmakers they hire to fulfill their unique visions of their respective franchises, and that their iterations will be left alone. If history repeats itself, then we are in for another fresh take on the World’s Greatest Detective. It will be wonderful to see what Reeve’s Batman inspires within us, and while there’s plenty of uncertainty as to what 2021 will look like by the time we see the film, we can rely on Batman to endure with us and become something else entirely: “Legend, Mr. Wayne.”

Comments