The Loyal Legacy of Bond: Skyfall

“Sometimes the old ways are the best.”

The list of films that have been screened at the White House and by extension Camp David is staggering. It is effectively a list of every major studio release of the last 50 years. While some presidents were bigger fans of one genre over another, every president since has kept up with the longest running film franchise in history: Bond. It’s not hard to see why the character was such a hit with the Oval Office. Kennedy (the first president to get see Bond in 1962’s Dr. No) famously wanted 007 on his staff, but our guy Ron had this to say about the iconic spy: “I’ve been asked to state my feelings about a fellow named Bond – James Bond. Well, as I see it, 007 is really a 10… our modern-day version of the great heroes who appeared from time to time throughout history and who put their lives on the line for the cause of good.” The simplicity of Reagan’s take is a fascinating paradox. It is both an essential aspect and a misleading platitude about the nature of the character. It’s not an insulting description by any means, but it is worth re-examining how we may come to understand Bond as a symbol for national pride and an example of true patriotism, and using the rich text that is Skyfall to do so.

In Dr. No, Bond is introduced to us in a brightly-lit casino; in 2012’s Skyfall, it is in a shadowed corridor, effectively telling us that the world that Bond inhabits has changed. This theme has been explored to varying extents throughout the franchise, but Sam Mendes’ Skyfall tackles it with the full force and expertise it demands. The chase scene that ensues has Bond going after a hitman who has stolen a list of MI6 operatives cover names. Bond’s pursuit is in the glorious fashion we have come to expect from him; a thrilling sequence that’s in the pantheon of pre-title Bond action scenes. What makes it stand out, however, is not the escalation of car chase, to bike chase, to train fight (there’s also a bulldozer in there somewhere), but how it pulls the rug out from 007. The target escapes after Bond is on the receiving end of friendly fire by fellow agent Eve (Naomie Harris), and his unconscious body is carried by water stream into the apocalyptic opening credits (shout out to Daniel Kleinman’s main title design) whilst Adele’s Oscar-winning title song serenades us with the lyric “This is the end.” What we are starting to realize is that the film has something on its mind, and is using 007 to express it. The formula is Bond, but the execution is something else entirely. We are left wondering for the first time in the series: “where does Bond go from here?”

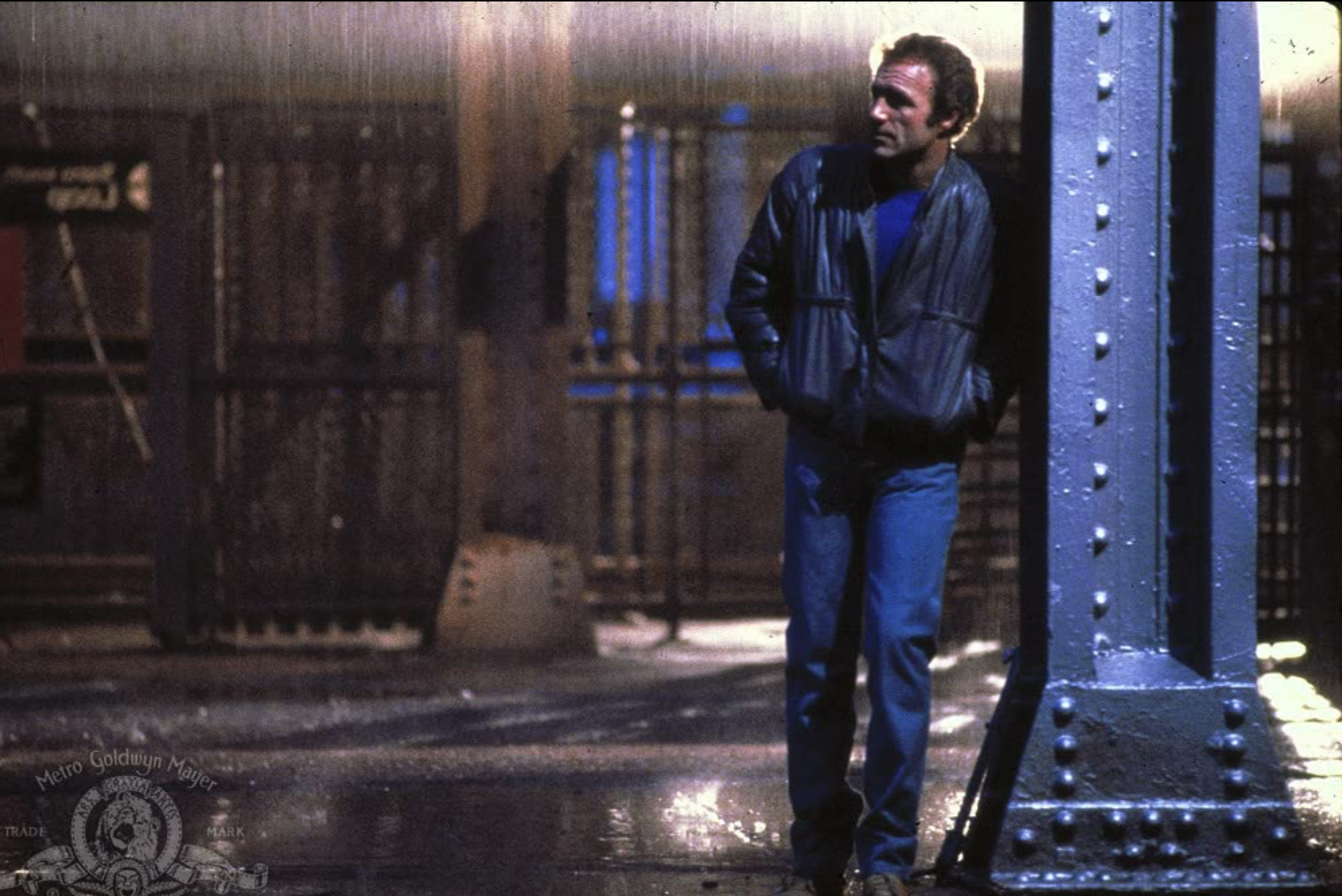

On the surface, it’s easy to see why Mr. Reagan took a liking to Bond. He stops rogue political entities and evil despots from threatening world peace and he does it in the name of his country. What keeps this theme fresh is the film’s expression of how isolating his line of work is. From his colleagues’ disapproval of his lifestyle, to his predication to self-medicating with alcohol and painkillers, we understand that his patriotism does not come for free. However, Daniel Craig’s nuanced “show not tell” performance is the real indicator that Bond himself questions his role in the world. He routinely puts his life on the line for bureaucrats and company men, and to what end? So that he can be shot off of a moving train because his boss gave the order to?

If he did not prove it to you in his first two outings, then Craig proves it this time: he is the best actor who has ever played James Bond in a film. There, I said it. The toll his duty has taken on him has forced him to be introspective, and Daniel Craig is up to the task of taking us through James Bond’s psyche. Although 007 takes advantage of his KIA status and hides out on the Turkish coast, the same duty he tries to escape is what brings him out of his pitiful “retirement.” When the news breaks (on CNN, which is conspicuously playing in a bar off the coast of Turkey) that MI6 headquarters has been the target of a terror attack, Bond cannot help but answer the call to arms. The war has been brought home, and he cannot help but finish the fight he selfishly wanted to leave to someone else. That someone is M, played masterfully by Dame Judi Dench. Bond makes his return known by confronting M in her home for choosing the big picture over his life. The acting showcase that ensues is one for the ages, and as much as Bond protests that him and her are both “played out,” M sees things for what they are: the world we once knew is under attack, and they need Bond to fight for it (sound like anyone we know?)

The threat that faces M and the British government is new to them, just as the threats Reagan faced in his presidency were unlike anything we had faced before. In the franchise’s past, Bond had faced many foes who acted in the name of their country, or worked with a foreign power to serve their own private interests to destabilize global politics. Auric Goldfinger worked with a Chinese nuclear physicist to attack America’s gold reserves, Franz Sanchez distributed Columbian drugs with the help of some bent CIA operatives, and every villain that Brosnan faced off with worked with some rogue agent to do something to natural resources or the global economy yada yada yada yada (for the record, I think Pierce had great baddies in all of his outings. The 2020 media could take a sobering look at news mogul Elliott Carver). Even Craig’s first two baddies had similar plans, albeit much more realistic. But with Skyfall we are graced with Javier Bardem’s second great cinematic villain: Raoul Silva. Both a personal favorite of mine and a franchise high point, Silva only has revenge on his mind. His introductory scene is once again Bondian in formula, (James allows himself to be captured so that he may face the evil he has been chasing) but the execution this time is closer to art-house cinema; a single take of Silva walking from one end of the room to another delivering a monologue from playwright/screenwriter, Jez Butterworth. You can tell Craig and Bardem had fun shooting this one, they’ve been given an actor’s playground full of masterful text.

In 1995’s Goldeneye, Sean Bean’s disgraced 006 made for a great foil, but Silva is truly the antithesis of Bond. Like every great (and trite) protagonist/antagonist relationship, they are simply two sides of the same coin. Bond is forced to look in a mirror and see what he could have become if he had one bad day too many. After Bond follows the trail of the stolen list to Silva’s remote island, we find out that Raoul is a former 00 agent, and that he blames M for his misfortunes. “Look at what she’s done to you,” Silva claims. “I made my own choices,” retorts Bond. The way Silva needles and toys with Bond feels habitual. By the way Bardem’s prideful eccentricity holds us hostage, we know that this tactic has worked on weaker agents before. He believes a countrymen’s faith to be fallible and he proves this by mocking the idea of true belief, and feigning the idea of liberating Bond from his stately shackles arguing he could “pick his own secret missions.” But we know James better than Silva does, and we know that his “pathetic love of country” (great delivery by Craig here) comes from a deeper place that Silva can only pretend to understand. This feels less like a political statement intended by the filmmakers, but seven years following the film’s release amplifies the idea that a patriot is persecuted for being loyal. It has become taboo to express your national pride, so seeing a film so confidently express these attitudes feels (retroactively) refreshing.

As good as the first half of the film is, the back half becomes great after Silva is captured. While held in captivity, it is revealed that M gave up Silva to the Chinese government for illegally hacking them back in the 90’s. She got six agents released from prison in exchange for Silva, who was forced to endure years of torture. Silva’s revenge plot starts to make more sense, as we now understand that what he’s doing to current MI6 agents, has been done to him: exposed and left for dead. Whilst Silva believes himself to be righteous in this endeavor, he is more closely related to a war criminal wanting to exact selfish revenge on M for abandoning him. We understand his point of view (betraying the men and women a government uses to fight its battles is a truly heinous crime), but we disagree with the ways Silva has chosen to cope with his demons.

In another brilliant chase sequence, Silva escapes and tries to fulfill his mission, with Bond reliably in pursuit. Their collision point: Trinity Square, where M has been summoned to court to answer for the MI6 security breach, a fitting place for the film’s character’s to fight for their respective sides of justice. M’s testimony can be summated as an argument for why individual agents with boots on the ground are still necessary in the modern age. When your enemy does not wave a flag and fights covertly, how can you expect to win playing by obsolete rules? M quotes a passage of “Ulysses” by Alfred Tennyson, that is played as voiceover as we see Bond relentlessly sprinting to the court room. The poem, which talks of heroism and willpower, coupled with Thomas Newman’s triumphant score (the track aptly named “Tennyson”) creates an emotionally gratifying crescendo that takes the form of a shootout between Bond and Silva, with M tragically caught in the middle. The scale of the sequence is small, but the stakes could not be greater. True justice hangs in the balance as Bond fights for who and what he cares for most in the world.

The film travels to Scotland for the finale, and earnestly reveals the meaning of the film’s title to be the name of Bond’s ancestral home. We learn that when Bond had nothing else in his life, he still had his sense of belonging to the United Kingdom. He’s been playing Silva’s game for the entire film, and it takes him going back to his roots in order to gain the tactical advantage, and to remember why he signed up to be an agent in the first place. Holding his father’s old hunting rifle, he gets his deadeye accuracy back. Revisiting the hollowed corners of the estate, he discovers opportunities to trap his enemies. Reuniting with the family gamekeeper, Kincaid (the late and truly great Albert Finney), he is reminded of the things he appreciated about his orphaned childhood. The finale is a desperate game of “defend the castle” where Bond must use his wits and his knowledge of the environment to defend his home against Silva and his forces. Some may argue that the creation of Skyfall lodge removes some of the mystique of the character, I’d argue the opposite. It creates more mysteries than it does answer questions. We have vague ideas of what his up-bringing was like, but there are no contrite “this is how I’m feeling” monologues from Bond. Instead we look to his behaviors for clues of understanding his state of mind, as he reoccupies the space that he has tried so long to forget.

2006’s reboot of the franchise with Casino Royale made for a whole new dialogue between Bond and the audience. By stripping down the eccentricities of the series in favor of the spirit of Ian Fleming’s original novels, they opened the door for new thematic possibilities. Say what you want about the ’08 follow-up Quantum of Solace, but there is a clearly defined arc for Bond that is nicely book-ended in that film. Skyfall takes the ideas of the first two Craig films to their surprising yet logical conclusion: Bond is a man who was robbed of his adolescence, and was forced to create his own rules. His parents, the people who were meant to nurture and guide him, died in a tragic climbing accident. In Casino Royale, the woman he professes his love to and considers leaving the agency for, betrays him. When he is unable to save her, he is once again abandoned by someone who he thought would be there for him. It is no wonder he treats women, booze, cars and all of his other vices with such frivolousness; he cannot expect to rely on any of them for fulfillment. When everything else in his life failed him, England did not. His cultural identity existed when he faced true adversity, and it will remain as long as he is willing to protect it. If M represents his devotion to the ideals his nation holds true, then her death after the battle is won is the greatest form of loss he is capable of experiencing. He is once again abandoned, fulfilling the tragic cycle he is all too familiar with. The punishment for questioning his faith is losing her, and it is a price he will never allow himself to pay again.

Our Guy Ron’s assessment of Bond as someone who put his life on the line for the cause of good, has never carried so much weight as it does with Daniel Craig playing the role. He is able to validate the character’s history in a way that none previously could. It is believable for an audience to see Craig truly devote himself to a higher cause. James Bond has been used as a defining icon of masculinity, and the magic trick the film pulls off is examining what makes this man who he is, and challenges his relevance in a way that fortifies his iconography. It is at first disconcerting to see James Bond on his worst day struggle to shoot a paper target and do pull ups. It is also extremely comforting to see how he breathes new life into the things he is so familiar with and desensitized to. Even on his worst day, he is able to rise above his shortcomings and fight for the cause. When no one else trusts his ability to get the job done, it makes no difference to him, the job must be done.

Every human being is fallible, and when Bond is invincible he is no longer relatable to the audience. There are extremely entertaining aspects of every entry in the franchise, but if Skyfall taught us anything, it’s that sometimes you have to go away in order to come back. The solution to our own suffering is within us and looking inward is vital to discover the answers to the hardest questions we ask ourselves. Without that kind of self-effacement, would Ronald Reagan have been able to accomplish all that he did? Surprisingly enough, we can look to 007 for insight. When the opposition was at their fiercest, these icons did not back down when their resolve was tested. I hold Reagan’s above sentiment to be true; James Bond represents the remarkable and historic individuals who are able to take their subjective feelings, and work towards objective good despite them. I look forward to Bond’s return, I look forward to what new ground the franchise breaks, and I hope that Bond will continue to do the job he was born to do “with pleasure.”

Comments