“It Starts in the Home”: Run Hide Fight

When independent film producer Dallas Sonnier first came on the scene in 2015 with the western/horror throwback, Bone Tomahawk, he started a pattern of funding challenging, “right of center” genre-filmmaking. Since then, he has put out increasingly overt political commentary with films like Dragged Across Concrete and The Standoff at Sparrow Creek. These films tackled the issues of policing, infringement of government on its people, and the justice system in America, all from the perspective of right-leaning filmmakers. Sonnier had come under major scrutiny in the summer of 2020 when his producing collaborators were accused of predatory sexual misconduct on set of his films, and he himself was accused of protecting the accused within the hierarchy of his production company. Here we are six years later, and Sonnier’s most recent project, Run Hide Fight, may be his most inflammatory yet. It’s as complicated a film to discuss as the circumstances surrounding its production and release, but that isn’t going to stop us from trying.

If someone is involved in a film that tackles social justice and societal troubles, then during the press tour they will be undoubtedly be asked time and time again; “How do we solve the issue of ___ in America?” In regards to the dilemma posed by mass shootings in schools, you’ll usually see actors give a spectrum of answers in regards to the place of the Second Amendment. This will always be a losing battle, because these questions are ultimately designed to get buzz-worthy answers. The premise behind; “How do we stop school shootings?” is understandable but flawed, because it implies an absolutist approach that isn’t exactly realistic, and doesn’t imply a solution. A better question is; “How do we prepare for the worst of circumstances to the best of our ability?” Once you answer that, your follow-up may be; “Where do we accomplish that?” Run Hide Fight offers an answer to the latter question by saying that it starts in your home.

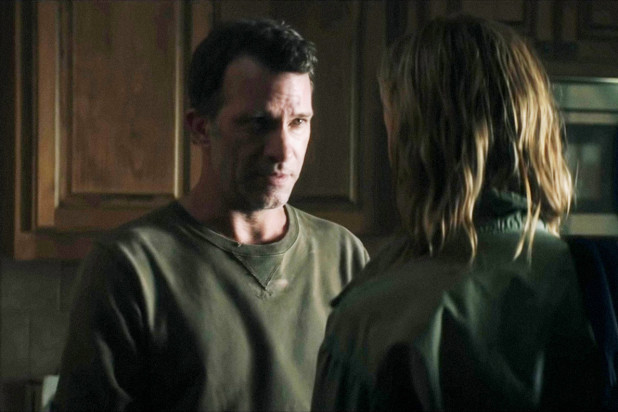

The film follows Zoe (Isabel May), a 17-year old about to graduate from high school who could not be happier to leave that part of her life behind. It’s revealed that her and her father, Todd, (Thomas Jane) suffered the loss the matriarch of the family (Radha Mitchell) to cancer, and her passing has strained their relationship. It’s clear that she was a good mother and that Todd is doing the best he can to connect with Zoe, even going so far as to teach her to hunt for game, properly handle a firearm and impart his knowledge acquired during military service. When Zoe goes to class on senior prank day, she gets thrown into the Die Hard scenario as the de facto John McClane when a few deranged students take hostages in the school cafeteria and try to make their attack the deadliest school shooting in history.

From a film-making standpoint, Run Hid Fight is a highly effective B-movie. It makes the most of its low-budget and it has impeccable art direction and cinematography that keeps things simple but tense. However, it also has the baggage of dialogue that belongs in a student film. It has all the atmosphere and intrigue reminiscent of a John Carpenter thriller from 1981, but without the script to fully explore the world it builds. The unique bend to Run Hide Fight’s core is the way it empowers Zoe through her upbringing. Her desire to save her classmates and skillset to do so were instilled by the parenting of her mother and father. When Zoe is forced to match the violence of action by the attackers, it’s obvious how her father’s parenting kicks in. When she is forced to reflect upon the violence and her feelings towards it, she imagines what her mother would have to say about it. It’s an effective and efficient screenwriting device that conveys the various ways Zoe hasn’t dealt with her own trauma and also how she must literally and figuratively fight for survival.

The political statement of the film is far less overt than the critics would lead you to believe it is. The low-hanging fruit would be for the film to claim that if the teachers and security guard at the school were armed, then none of this would be possible . The flawed part of this premise is actually the other side of the same coin of the “people kill people, not guns” argument. If people kill people, then people defend people (although the threat of retaliation to crime is part of the equation to a lesser degree). The film posits that it takes a person that is trained, prepared and courageous enough to save others. If raised in any other household, Zoe would be just another hostage, but coming from the family she does makes her both an empath and a warrior. It’s this choice in the writing that makes the film rise above being conservative snark or even just plain nihilism.

The untapped potential of the script is in its villains. One of them has a pretty effective and nuanced character arc that gives pathology to why he chose to take part in the attack, but the rest are extremely underwhelming. Not only are their performances grading, but the film has the opportunity to explore their home lives’ the way that it explores Zoe’s and doesn’t take it. There’s a difference between giving attention to evil people who don’t deserve it, and connecting the dots to understand what must go wrong in a person’s upbringing to make them capable of cold-blooded murder. To clarify, this is not a ruling to say that all villains must be relatable (in fact it’s a huge problem in modern cinema, mostly thanks to Disney and Marvel), but there must be some sort of pathology to their characterization that makes sense to the viewer. Currently, Christopher Nolan is the best at this as he makes villains that are undeniably an evil that must be stopped, unjustifiable for their deeds, but have an internal logic that the audience can trace the psychology behind.

Despite the film’s shortcomings, it’s message about self-defense as a delicate balance between ethics and capability comes through clearly. The unfortunate thing is that the film is likely to be a casualty of the culture war against problem-solving, independent thinking and family dynamics. In the eyes of the Left, the film’s desire to present preparedness as a solution to violence is the antithesis of the free-thinking they have unofficially outlawed in America, and thus it is part of the problem in their eyes. Meanwhile, they decide who the villains of society are for us, and use discourse to sick us upon each other for being on the other end of the political spectrum, rather than be proactive or solution-oriented. The people who get left behind by this are our children, who are left to fend for themselves in their classrooms, at their lockers, in the lunch room, on the playground, or in the principal’s office without their parents’ guidance. While we’re busy arguing with each other on the internet about whether or not schools should reopen, they’re stuck at home and left emotionally defenseless.

Comments