Disney and Marvel: Should We Sympathize With the Enemy?

“Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly are ravening wolves.” – Matthew, 7:15

A hero is someone who has the courage to do what most others would not. Film used to largely be our way into their psyche. Villains always interested us and you could not have an effective hero/protagonist without an equally effective antagonist. Darth Vader, Hans Gruber, Biff Tannen; all classic bad guys that make us excited to revisit the films they belong to. However, something changed between 2007-2009. The audience became more interested in the villains than the heroes. This change in focus was reflected on television as well with Breaking Bad also premiering in 2008. This period in time led to a renaissance in evil archetypes, but it also allowed dubious agendas to Trojan horse their way into mass entertainment.

In 2007, No Country For Old Men made Javier Bardem a household name with his chilling turn as cartel hitman, Anton Chigurh. In 2008, Heath Ledger gave the Joker iconography its definitive screen presence in The Dark Knight. In 2009, Christoph Waltz was the cunning and charismatic Nazi detective, Hans Landa, in Inglourious Basterds. Each one of these three actors gave, far and away, the most memorable performances of their respective years. Audiences, critics and awards-ceremonies were all in full agreement, and set a new precedent for studio-filmmaking. The villains HAD to become a bigger focus, and whilst it took the Marvel Cinematic Universe quite some time to catch up to this trend, they found their way into the it.

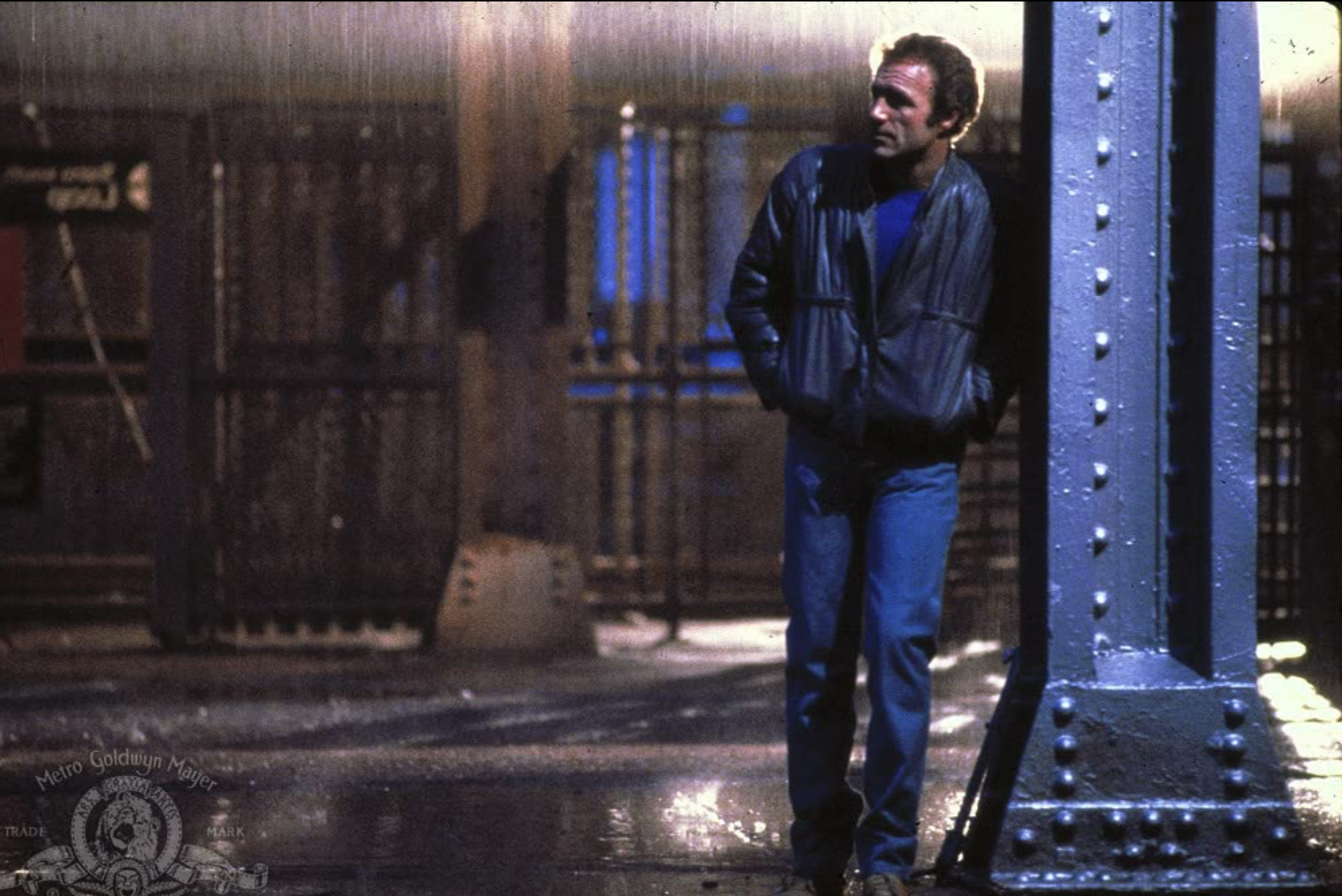

We’ve alluded to this before, but just to reiterate, in order for a screen villain (or any character for this matter) to be compelling or watchable, they must have an internal logic that the audience can understand. It is not required that the audience agree with the villain’s logic or pathos, but sometimes you can. Good and evil are relative positions, and the perspective can be manipulated by the story teller quite easily. Michael Mann’s Heat is a great example of this, as the film is built upon the equality and dual-focus of its two leads, and questions who is truly good or evil. In more clear cut terms: the villain you sympathize with is someone like Darth Vader who was manipulated and coerced into being evil, and the villain you don’t agree with but enjoy watching is Hans Gruber.

We all know that a company like Disney likes to have its cake and eat it too, but the way they have portrayed villains in a few key Marvel films feels more sinister than simple corporate greed: they feel like propaganda. We’re talking specifically about Black Panther (2018), Avengers: Infinity War (2018) and Avengers: Endgame (2019). The two villains in question are Erik “Killmonger” Stevens (Michael B. Jordan) in Black Panther, and Thanos (Josh Brolin) in the latter two Avengers iterations (although Thanos had appeared in various cameos in prior films). Before we go into the troubling designs of these two characters, it’s worth briefly clarifying our position on the films they belong to.

Ryan Coogler, writer/director of Black Panther, is clearly a well-meaning and highly talented individual who has absolutely earned his success as a filmmaker. His intent to create a big-budget, predominantly black cast-superhero tentpole film was admirable. The film doesn’t fully reach its potential, but its a far more cohesive/interesting film than most of its Marvel counterparts. Anthony and Joe Russo, also co-writers/directors, had a huge task in front of them with bringing together as many characters as they had in the final two Avengers films, and whilst Infinity War was largely a poorly-paced, unfunny overrated slog for most of its runtime, Endgame was not. In fact, Endgame was far more compelling, humorous, emotionally-charged and even well-paced despite being a three-hour investment.

All of that being said, there’s a rather large bone to pick. Killmonger’s ultimate plan in Black Panther is to take the advanced weaponry/technology of the fictional secret-African society, Wakanda, and use it to invade the western world. More specifically, deliver it to people of African descent so that they may use it upon their oppressors. When our hero, T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman), foils Killmonger’s genocidal plot, then his takeaway is to share Wakanda’s ingenuity with the world by joining the United Nations. As we can see by the cultural response by the film, the character of Killmonger was praised as one of Marvel’s best villains up to this point, with so many people going as far as to call him empathetic. They found his point-of-view to be highly relatable: a black man from Oakland who sought to equalize the racial status quo with lethal force. Again, Ryan Coogler’s script clearly believes that the titular character has the winning philosophy. That being said, the acceptance of Killmonger’s plight by the Left-sympathizing fans of the film calls into question what Disney wants our takeaway from the film to be.

Now we turn our focus to Josh Brolin as Thanos, the overarching bad guy of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Slowly but surely over the course of the franchise, his threat loomed near and fans eagerly awaited his challenge. His plan: to use a reality-bending device to eradicate half the population of the universe. His reasoning? Because there are not enough resources in existence to sustain the amount of life that is out there. The rationale behind the performance of this character on screen, was to portray him as a self-proclaimed altruist. Brolin plays him as a teacher of sorts, and the Russos write him as a protagonist in Infinity War, the first part of the series two-part conclusion.

What Disney is effectively subverting into its entertainment are Leftist philosophies like “racial justice,” “population control” and the “UN/one-world government” agendas. By writing villains to be one step further than “understandable” and making them “relatable,” Disney is able to indoctrinate its considerably large audience of young people. The paradox behind film is that it is almost impossible to separate the agenda of the filmmaker from the film. How can you follow a film without a point of view to present the story from? Where do we draw the line between a film thoughtfully illustrating its point of view and trying to bludgeon a message into your own thinking? When does the manipulation of the audience become unethical?

If we did not know about the bastardization of racial justice or the climate change/population reduction agendas by the hands of the Far Left, then perhaps we could simply watch Marvel’s filmography with some leeway as to what they were trying to teach the audience. There are worthy discussions to be had about how to protect America’s citizens from persecution for superficial reasons, because clearly the First Amendment is not being respected enough to account for this. Disney is the exact kind of corporation the Left claims to be trying to undermine, but they still go to see these movies in droves and find resonance in their messaging. Similarly, the question of technological innovation and resource management is a necessary one, but the conclusion that we must remove people in order to accomplish that could not be any more sinister.

We find ourselves in this moment when the culture war is in full swing against liberty, with cinema being used as one of many tools to wage it. It’s clear that how we’ve been voting with our wallets has only been empowering the enemies of freedom. The thing that is both consoling and discouraging about this dilemma, is that it’s nothing that hasn’t been seen before. Certain films that go against the grain, or speak to an agenda not aligned with the media elites have been attacked many times before. Take Fight Club for instance; vastly underperforming at the box office for arguably political reasons, only to be later heralded as ahead of its time and to be accepted by an audience seeking truth amongst noise.

Comments