Expectation, Forgiveness, and Rebirth in Born on the Fourth of July

We at MRV want to make a birthday shout out to Tom Cruise today (July 3rd), and for Ron Kovic and America’s Independence tomorrow the Fourth

It probably is no surprise that we are choosing to discuss Oliver Stone’s 1989 master work Born on the Fourth of July this week of all weeks. Given the inflection point we find ourselves in at the current moment, there is no more appropriate film to use as a reflection piece for this coming occurrence of the July 4th holiday weekend, and no better example of what happens when expectations collide with reality.

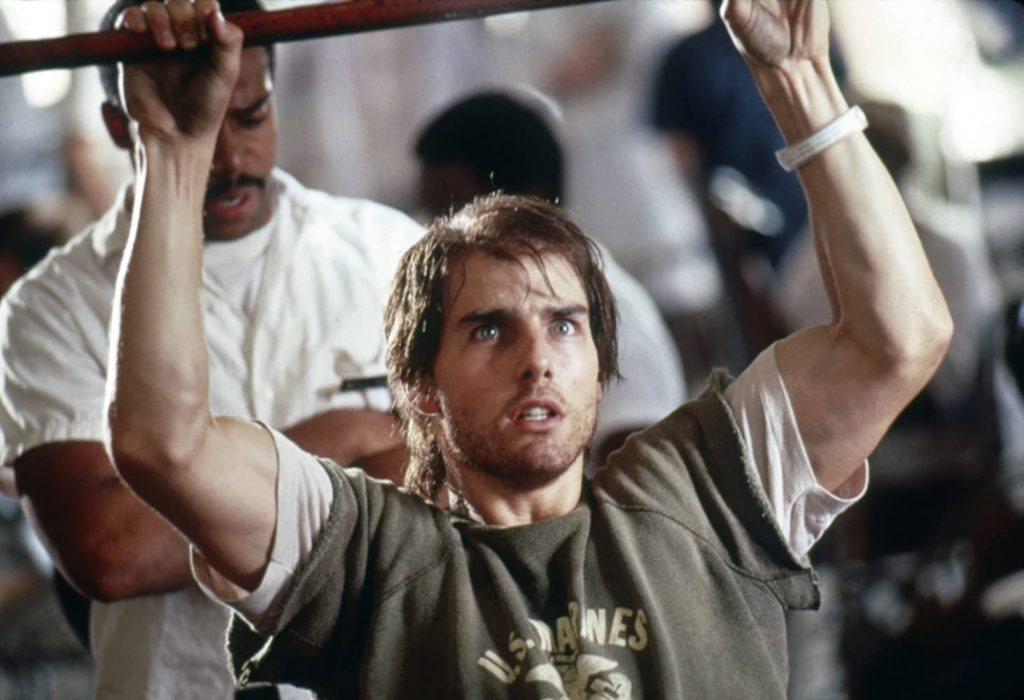

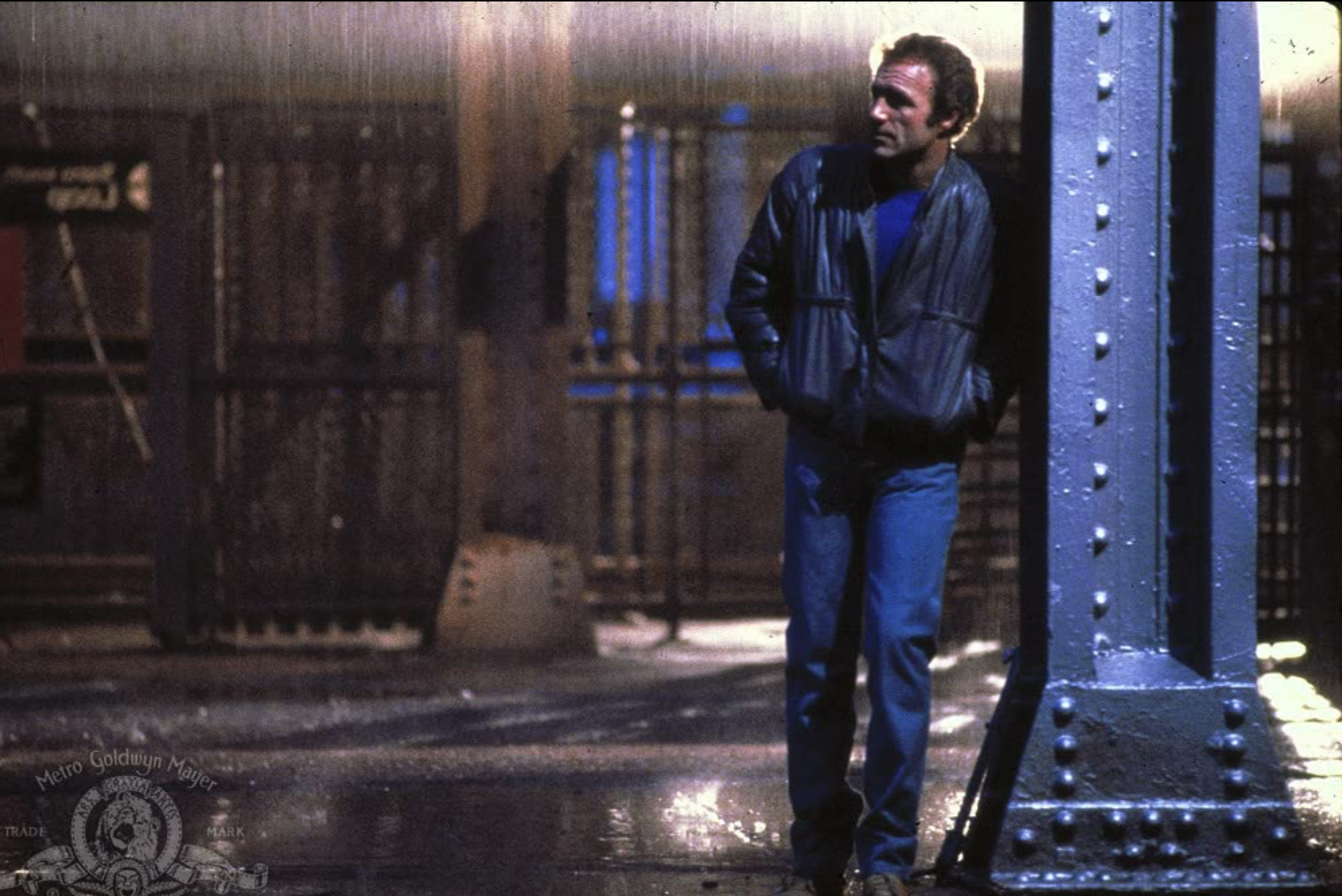

The film (based upon Ron Kovic’s autobiography of the same name) documents Ron’s strive for excellence as a child, his willingness to serve in the Vietnam War, and his turn to activism after being paralyzed during the conflict. It was already a critically-acclaimed book, and a screenplay that was shopped around Hollywood by director Oliver Stone for a number of years before he and his producer Paula Wagner settled on Tom Cruise to play Ron Kovic. Most people, including Ron himself, were skeptical of the casting. However, after Cruise met with Kovic in his birthplace of Massapequa, Long Island, he was certain that the young star was the right man for the job. Kovic was on set for a good portion of the shoot, and his input shows up on screen as the personal nature of the film really comes through the lead performance.

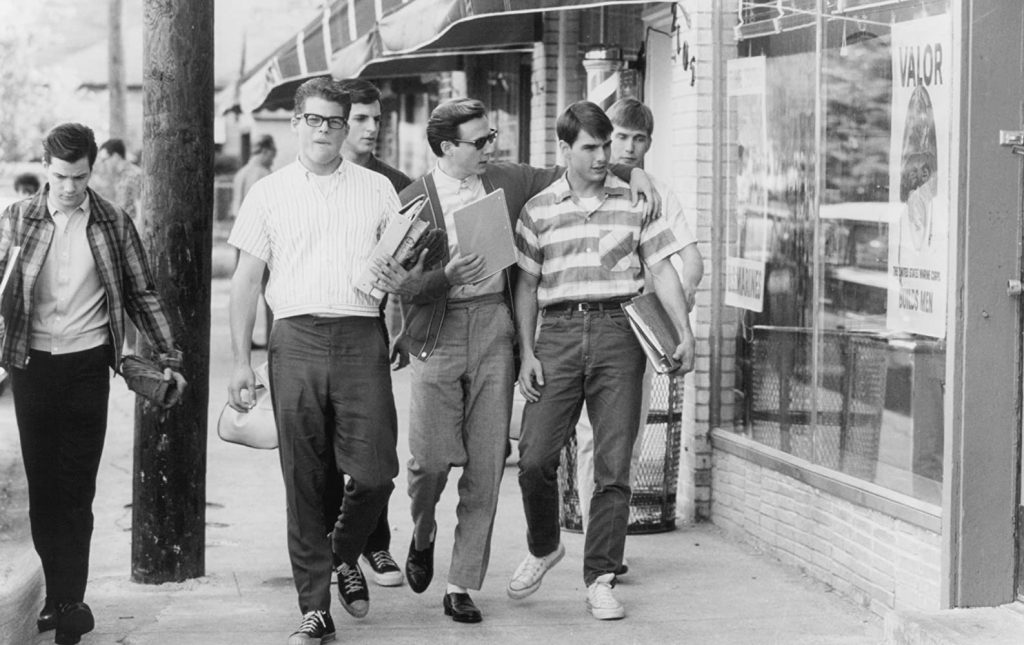

Cruise’s turn as Kovic marks a turning point in his career; his first time playing a historical figure, his second real turn in dramatic film (following Rain Man, the year prior), and the only film thus far that directly challenged and explored his status as an American film icon. The roles he had taken leading up to Ron Kovic were region-specific stories that could only have taken place where they were set. Risky Business (1983) is a distinctly Chicago suburb film, Top Gun (1986) can only happen in San Diego, and The Color of Money (1986) is without a doubt a Midwest winter road trip. The Kovic family is an East Coast suburban clan who put all of their money on the second eldest of their six kids: Ron. He was meant to grow up to be the best at everything: a sports legend, a war hero, a true American success story. However, what we know from real life is nothing is ever that simple.

After relentlessly training for his high school wrestling championship, he loses the qualifying match. After righteously volunteering to join the Marine Corps and fight for the nation, he is led to commit atrocities by his apathetic commanding officers and becomes paralyzed from the lower chest down by a stray bullet. When returning home to the Bronx VA hospital, the care conditions he and his brothers in arms receive are horrendously underfunded and unforgiving. It is arguable (perhaps even, likely) that he may have been able to walk again if the hospital equipment were more reliable, and the care staff were more diligent.

Once he is able to return home, he is met with sorrow from his loved ones, and disgust by the anti-war movement. Ron keeps his disappointment at bay for as long as he can, but eventually his anger takes hold. He dedicated his life to everything and everyone that he was raised to believe in, and those very same people and constructs betrayed him upon his return. If any of us were sitting in his wheelchair, we may feel similarly.

One of the greatest aspects of the film’s story-telling is its sheer efficiency. The film won the Academy Awards for Directing and Editing, and the pace of the film is absolutely deserving of those accolades. In two hours and twenty five minutes, we experience Ron’s journey through hell and back in a comprehensive and intense manner. His despair, anger and shame are all so palpable because we clearly see the effort that Ron puts into every aspect of his life. The highest form of acting is as physical performance without the need for dialogue. With a look, with a gesture, with a single facial tick, Cruise puts us instantly in Ron’s head, and the legendary cinematographer, Robert Richardson is there to keep things cinematic and focused. When people discuss the power of cinema, you can point to any moment from this film, big or small. Even something as simple and Americana as a Kovic family dinner in a wide camera shot can exemplify the glory of anamorphic film.

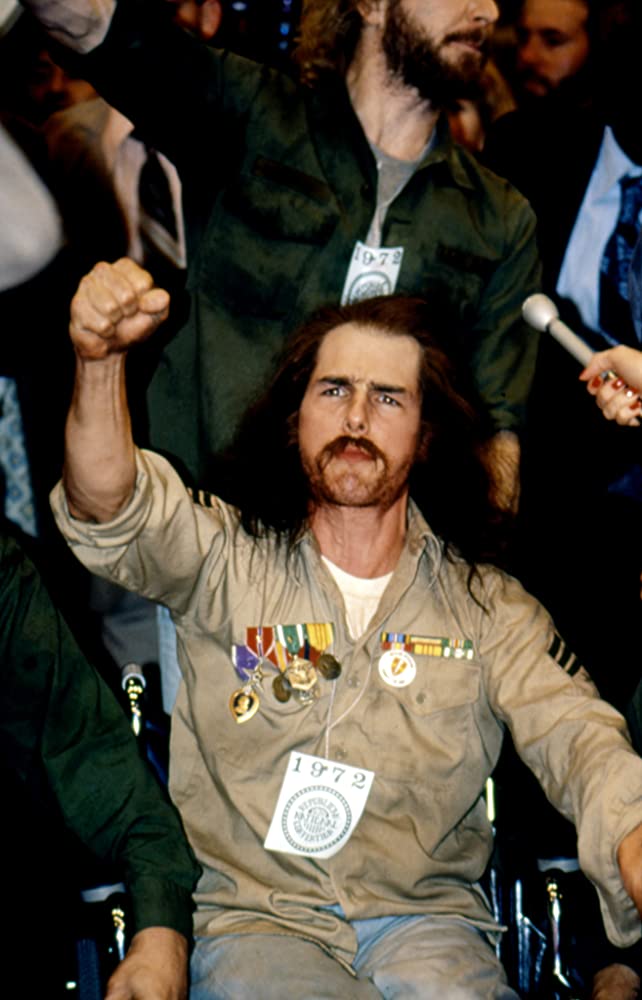

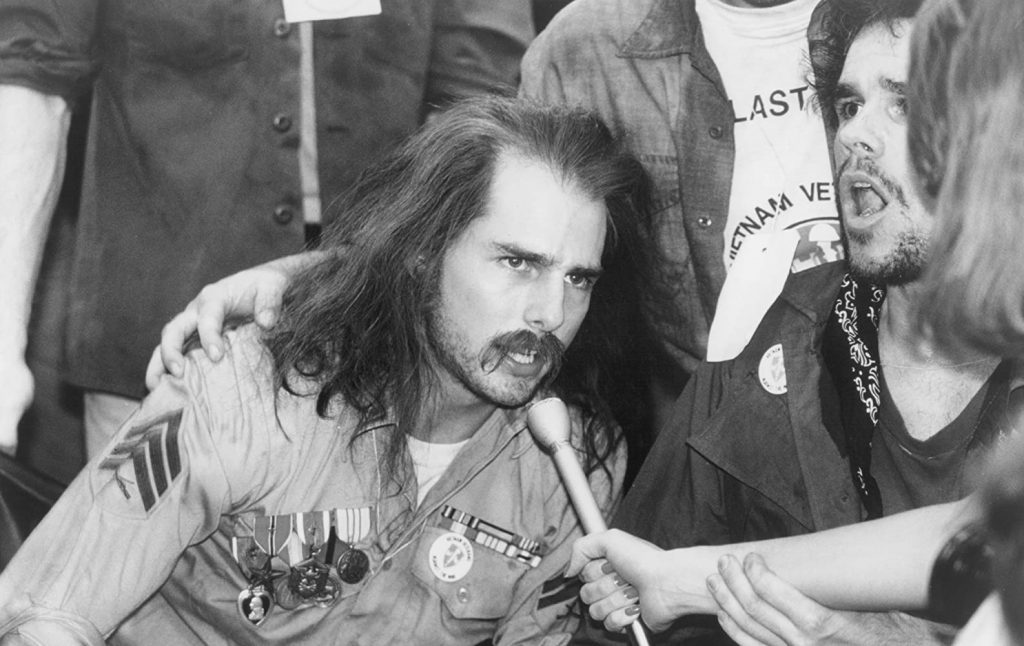

This film is very similar to other biographical pictures of this era in that it does not have a plot, per se, so much as it has a series of events in the subject’s life that led them to a newfound attitude and how that attitude changed the world around them. For Ron, it’s how he at one point advocated for the Vietnam War in order to protect the Western World from communism, only to become an anti-war activist after his experience in war. He felt lied to when his squad leader ordered him to attack a village of civilians under the pretense that the enemy was hiding in it, and he felt even worse when he accidentally killed a fellow squadmate in the same battle. When he tried to report both incidents to his CO, he was told that they would be swept under the rug to avoid doubt or scrutiny within the ranks. This guilt gnawed at Ron for years before he ultimately decided it was time to do something about it and join the movement for peace and atone for his mistakes.

The parallels between this film and the current climate in America are obvious, but perhaps more nuanced than ever. The Hippie movement was largely concerned with the same things, and it is a worthy argument to say that there was a genuine desire for unity and preservation of life at the heart of it. The same cannot be said for all sects of the current wave of protesting. When people peacefully resisted the national lockdowns and restrictions on individuals and businesses in recent months, they were shamed as indifferent to killing the elderly and people with compromised immune systems. However, if you protest in the name of a cause that the extremist left approves of, there is nothing to worry about as far as getting other people sick is concerned. These concerns are not so perfectly a right and left division. There are factions of disagreement within each of these matters, and the distraction this creates allows those who may benefit from this division to continue to thrive.

The role propaganda has in Western society has not changed so drastically from the era the film documents. The media advocated for the war when their viewership, on the whole, agreed with the cause. However, their tune changed when it became politically and financially convenient to do so. This is where people become skeptical of protest movements that have agreeable sentiments. The majority of the nation can agree on the value of human life and equality, but when governments (whose agendas rival the public’s by nature), pander to these beliefs, then the nobility of these movements is lost. We would posit that choosing a side in a fight is not enough to protect against tyranny. The individual’s internal decision to engage in a higher quality of life is what leads to stronger community, and the freedom to make these decisions is exactly what the Founding Fathers were trying to protect from government overreach.

Upon returning from war, Ron is still resolute in his approval of the war effort, despite discovering that his own brother is in favor of the peace marches. “Love it or leave it” becomes Ron’s catchphrase for this time of his life, a line fed to him by the discourse and talking heads around him. In defense of Ron and many other veterans’ use of that phrase, those who have not served cannot possibly understand what it must feel like to put their life on the line for our freedom to express ourselves, only to return home and see them exercise that freedom against you. “Love it or leave it” is an understandable sentiment, but just as with any other worthy cause, when co-opted by a larger force, it’s credibility and meaning can be diluted by cold and uninvested interests. Ron retains his credibility in our eyes, not just based on the nature of his personal experiences, but because he came to the decision to be a peace activist when it was inconvenient for himself, rather than giving in to a mob of dissenters.

Ron’s role with his activism may have started with Vietnam, but the feeling from within that sparked this change of path was his anger of being used. He was willing to play the part in American culture that he was conditioned to play, but that path took him down the rabbit hole of despair and emptiness. Although we can understand and our veterans can directly relate to his given circumstances, what Ron specifically and ultimately accepts is that he chose to go to war. Yes, he was encouraged to be a certain kind of man by his parents and upbringing, but none of them explicitly told him to become a soldier. The solider’s life was his own idea of self-actualization, and that’s where his shame truly comes from. Ron decided to enlist and that put him in a position to unintentionally take the wrong lives. His subsequent choice to become an advocate for peace is bred out of his choice to forgive and better himself. As dark and depraved as he finds himself on this journey, and as sorrowful the audience may be for how things played out for Ron, the silver lining is that there is catharsis and inner peace on the other side of his turmoil.

We’ve discussed complicated real-life figures on this blog before, and although they make for highly entertaining films, some of these real people are far more complicated than their film adaptations. Take The Imitation Game (2014), a highly entertaining film that drastically idealizes a much more morally onerous subject than is portrayed. There may be something about Ron Kovic that the film glosses over or ignores, but it seems unlikely given how unflinching the screenplay is in covering his many missteps. That being said, this is a story of redemption and rebirth through the darkest period of a person’s life. A story of how a man can atone for their gravest innocent mistakes, and how the harshest critic can be the self. The only way towards growth is self-acceptance, and it is truly relieving to see Ron find that in the film.

“The Human Cost” is a concept that comes up in war films all of the time, but Oliver Stone and the team assembled for this film get to a much deeper level of that idea. The true cost of these tectonic shifts in the country is our misunderstanding of each other. The inability to separate nuance from division, and discover shared beliefs and commonalities is the genesis of turmoil. Revisiting our Constitution, we can see the common thread that the Founding Fathers were concerned with was preserving the examination of the virtues and nuances of opposing ideas from the malevolent side of human nature. These laws were designed to restrain the evils that exist within government from hijacking the communication of its people. What we see today is that a government doesn’t need to solely send troops to fight a war, they can bring the war home by pitting citizens against each other with the very rhetoric used by the people.

In times of peace and unity it may be easier to remember, but in times of doubt and fear it is vital to hold onto these values that we hold true. Cinema, at its best, can be a reminder of these values, and revisiting Born on the Fourth of July this year can show us that Ron Kovic had plenty of doubts, fears and faults of his own. What this film can remind us of is that we all experience those feelings as well. The thing that makes us unequivocally American is rising above our self-critical voices, forgiving ourselves for the times we have given into judgment and fear, and preserving a society that rewards honesty and self-effacement.

Comments